A workshop design in the making

How to disidentify with the technologist narrative

Disidentify: Not to identify with something; to reject a personal or group identity, etc. (Definition in Wiktionary)

Recently, I came across a job advertisement that sounded like it was written for me. The role was a “workshop designer” for a local independent collective that works on various community-focused initiatives. Their values align with the ones that I’ve been putting forward here. Furthermore, in my day job, I have been known to be able to turn most topics into workshop formats that help people tackle complex issues and arrive at decisions. I did not apply for the position for several reasons (it being part-time being the primary one) but designing and facilitating workshops focused on the topics of this publication is something I am hoping to develop and volunteer to deliver.

Hence, today, I will share thoughts on how I am thinking about translating some recent themes into a workshop format or two.

Disidentifying with arrogance

I have coined the moniker ‘recovering technologist’ to describe my personal predicament. Unexamined Technology has been an effort to see if writing about the various contexts of such a predicament resonates with others. I am motivated to extend the work into workshop formats, with the goal of giving tools to participants to uncover their inherent assumptions and to negotiate the different layers that go to into the technologist mindset; a mindset that seeks solutions via technology and is enchanted by technologies and their inner workings and what can be achieved with them, often without much criticism apart from toward other, competing technological solutions. The resulting tone is one of arrogance rather than humility.

A common belief that the latest innovations are always unproblematically superior represents another form of arrogance. It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that older technological innovations, ones that have become normalised in our lives (e.g. vaccinations or lighting), were adopted without debate. However, as historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz shows in his recent book Happy Apocalypse: A History of Technological Risk, the trajectories along which technologies have become accepted have never been straightforward. It’s just that the winners prefer such narratives to keep alternative solutions or inconveniences for profit-making at bay.

For Fressoz, the term disinhibition ”encapsulates the two distinct modes of technological action: reflexivity and disregard, contemplating danger and normalising it.” (Happy Apocalypse, p. 7.) His analysis is that throughout the history of technology, seemingly regulatory activities, such as standards, consultations, and health surveys, were presented as anticipatory and responsible risk management measures. But in actuality, they were retrospective patches to what had already been pushed through with a technology-minded political will.

Modernity has been hiding its traces, again. Again, it has curtailed our imagining, e.g., leading to inherent assumptions that past generations and communities surely could not have been wiser in their deliberations about adopting technologies. Following Fressoz, Machado de Oliveira, and others, my suggestion is that disidentifying from such arrogance is part of the work ahead.

Recovering through reorienting attention

If one is recovering, it is a process of recovery from something. When the object of recovery is from identification with technology, I suggest that the motivations for recovery stem from a recognition — an awakening — that our modern infatuation with technologies has not led us to a good place. This does not mean being anti-technology. Instead, it means ‘rehoming’ technology, as I’ve proposed in the past, to give technological solutions an amount of attention that is, in any given situation, correctly proportioned in relation to the context where such an action is taken. For example, in the case of medical emergencies, it is more than fair to leverage all the support from medical technologies that are at hand to relieve pain and sustain life. In such moments, attention takes the form of a moral act.

In contrast, claiming that ‘AI will revolutionise everything’ is an attention-grab in at least two ways: first, as a call to action in the name of technological determinism, and second, as a suggestion that much of our attention should now be spent embracing AI, and that it will inevitably consume our attention whether we find virtuous uses for it or not. This has already happened with our current always-on communication technologies and the resulting ‘attention economy’.

When harms are results from technologies that are not critical for cultivating or sustaining life and mutual wellbeing, directly or indirectly, defending the role that they take in our lives becomes less convincing. The more difficult questions about giving attention tend to arise when one takes a look behind the veil that often hides the systemic traces of harm. Too frequently, today’s technology development processes hinge on violence to humans and non-humans; violence that is buried under complex, faceless supply chains that are far removed from the monitors and meeting rooms where the requirements gathering, design thinking, and development takes place. Even when the experts in those rooms strive to address critical issues, the discussion is limited by the need to hold on, by minimum, to everything we have — the aim is, for example, to reach ‘energy efficiency’, i.e. optimise energy consumption so that we can keep using as much energy as today. If we were to reorient away from such a mindset, the problem-solving would shift towards ‘energy sufficiency’, i.e. an approach that necessitates using discernment about to which uses sustainable amounts of energy should be channeled into. Both approaches are not without their issues, but I wanted to bring up the latter as an example of the shift in mindset that the workshop attempts to facilitate.

Hospicing the inner techno-solutionist

We all tell narratives about who we are, both to ourselves and to others. Having worked in technology for 20+ years, I suggest that there is more than anecdotal proof that people working in the space, or enthusiasts of technology, identify strongly with technology, and therefore it figures prominently in their narratives about self. To keep the story coherent, one then needs to follow it through with how one attends to the world; through the lens of technology and its bedfellows, such as physicalist and atheistic worldviews.

The goals of the workshops have to do with the hospicing approach — to let the single-minded, ahistorical, and contextually insensitive forms of techno-solutionist thinking perish in a dignified way. A prime example of such thinking is Marc Andreessen’s manifesto about techno-optimism that proposes free reigns for technology development as the only solution forward, with underlying themes of unlimited economic growth, control, dominance, and profit — themes that Professor Hallam Stevens has rightly pointed out as colonial.

To wish for a dignified death for such thinking is to hold oneself back from othering Andreessen and his broligarchic buddies. It can feel like a thankless extension of empathy without reciprocity. Nevertheless, from such generosity, dignity arises. For me, the dignity arises from seeing technologies’ value only through their relations: there is no defibrillator without the need to make it available to the public, in the acute physical contexts where it might be needed. It only exists meaningfully in such contexts, and therefore ‘a right design’ for such a technology manifests in different ways: not only in the ones designed for emergency rooms but in the types of defibrillators that are easy for anyone to access and use from a kiosk at a street corner. The public body — importantly, a council or a charity — that has made the defibrillator available is an integral relation that makes the technology achieve its purpose and meaning through access. The device and its functionalities do not exist meaningfully in isolation, no matter how much it might appear so on the monitor where an engineer has designed its circuit boards. I do not wish Andreessen a heart failure on a street corner, but it would probably take that for him to buy into this relational view, not just intellectually but with heart, both literally and metaphorically.

The workshop format: first iteration

I have referred to Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s image of a dying olive tree in Hospicing Modernity, an image that “evokes the structure of modernity as an ancient elder facing the prospect of death” but willing to admit their mistakes and share wisdom about how to live differently. I suggest this is what recovering technologists should aspire to.

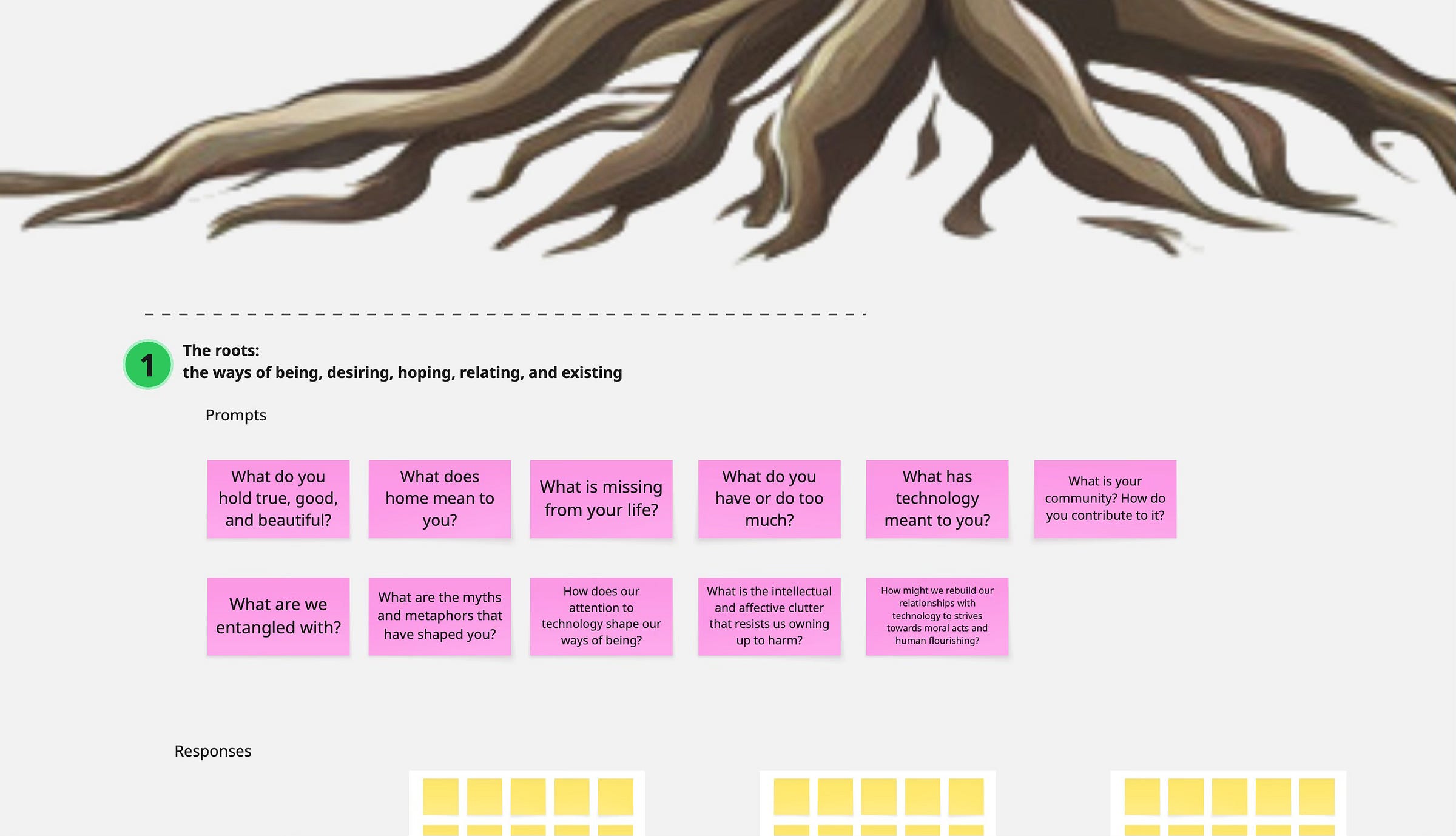

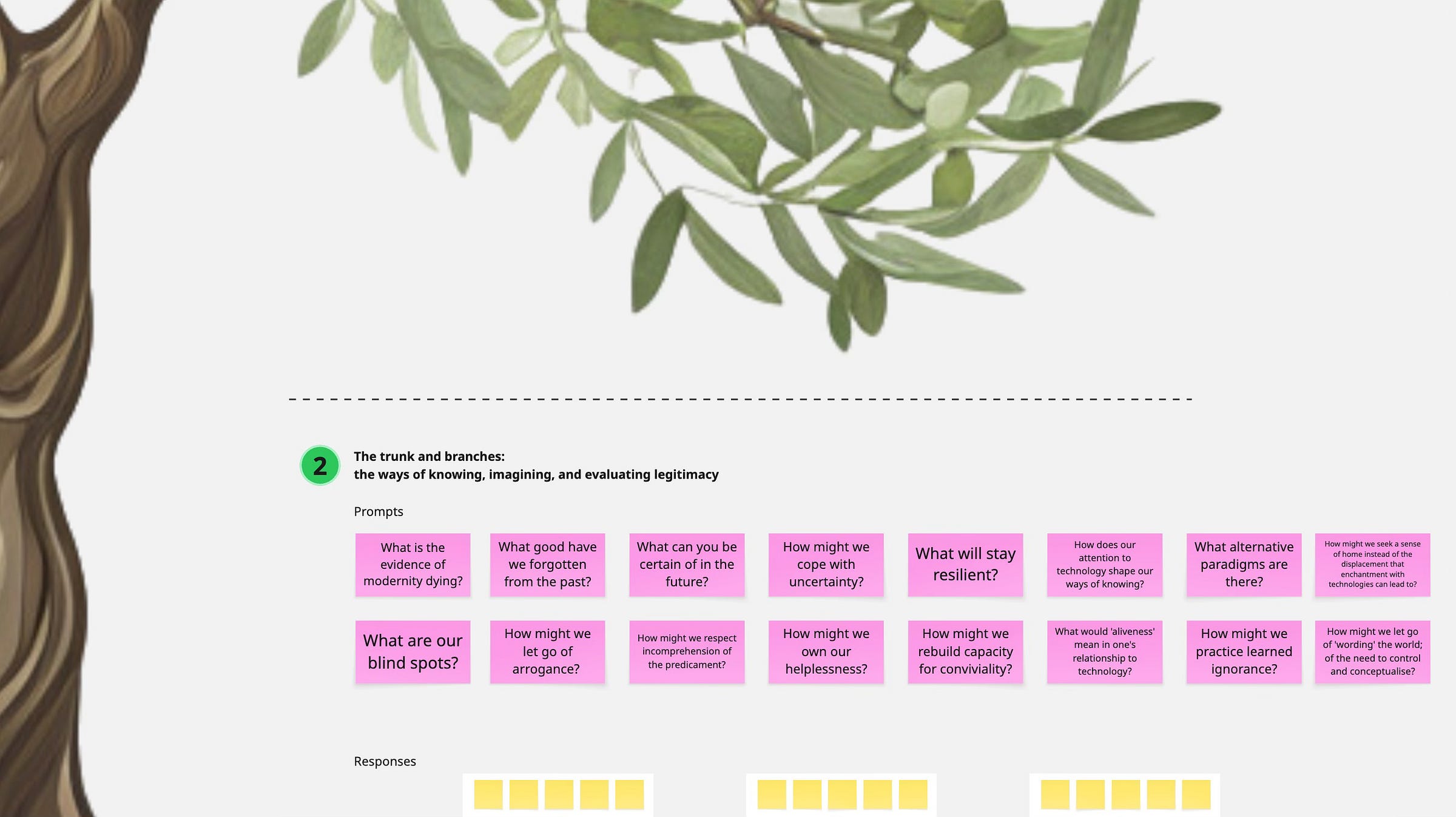

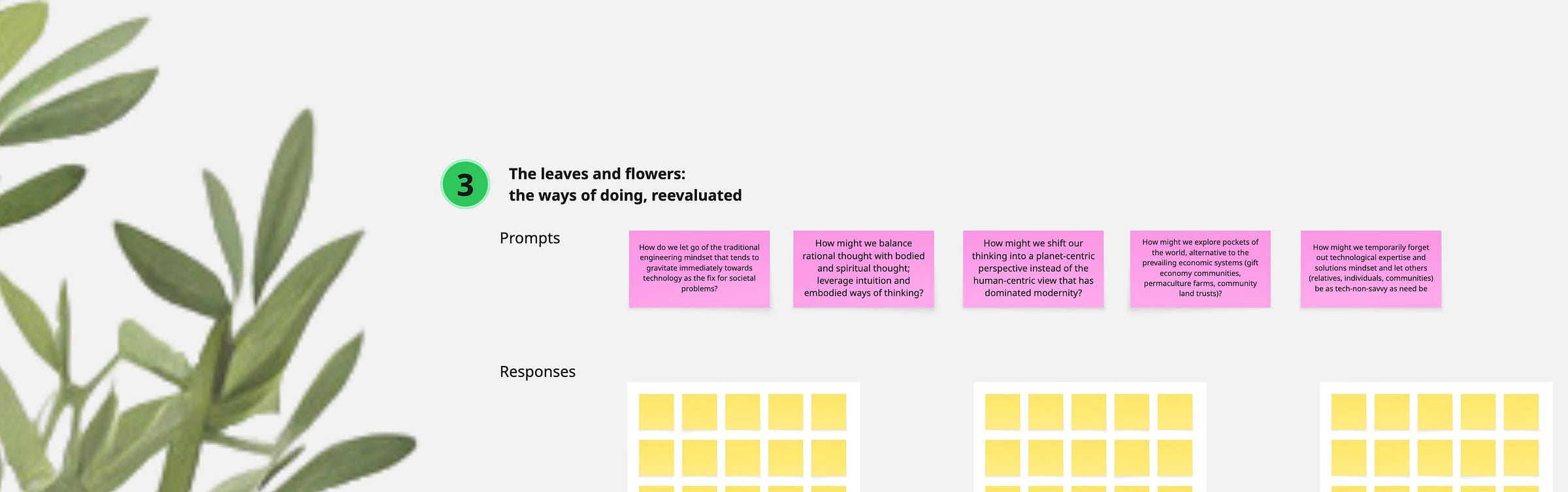

In the workshop design, I employ the tree as a metaphor that structures reflection about the types of attachments to one’s identity that would benefit from trimming and replanting. Below you’ll find an early design for how the elements of the olive tree shape the workshop activities — the image is from a Miro board designed for online participation, but the format can be run in-person as well. Each section has individual workspaces for participants to engage with prompts that are designed to evoke reflection on one’s technologist or technology-consumer identity. The prompts are also coined with the goal of uncovering hidden assumptions and raising awareness of the difficult predicaments that need facing, such as the threat of systemic collapse. In the sketches below, I have included a first set of prompts. They are tentative and somewhat inconsistent in their syntax for now, drawing from different prompt techniques, but hopefully, they bring the approach into life. In addition, I am planning for the workshop to have a pre-reading list as a means of orientation to the session.

The roots, the branches, and the leaves

The activities begin from the roots and move through the branches to the leaves. Let’s recap how Vanessa Machado de Oliveira defines the three layers.

The roots are the ontological-metaphysical layer; the ground of being from where the ways of being, desiring, hoping, relating, and existing in the world stems. This is where the workshopping needs to begin. Starting the other way around, from the leaves, the methodological layer that is about actions, would lead to soft reforms in thinking at best: the ideas would likely still be confined into the physicalist-materialist worldviews that most of us (global northeners) are conditioned into through educational and professional systems.

Hence, hospicing the inner technologist starts by establishing a critical technical practice. It involves letting go of a narrow worldview that values, for example, only that which can be empirically and technically evidenced and has utility according to modernity’s rules. Such valuing is often based on an unquestioned form of metaphysics, i.e. belief about the nature of reality as purely physical, formed of materials and their qualities that can be measured objectively from ‘a view from nowhere’, removing the observer with all their biases from the equation — something that quantum physics has questioned for a century now.

Yet, when engrossed in such metaphysics, it is understandable that it leads to solutionist dispositions. And building technology, as a set of applications of science from physicalist premises (never mind its blind spots), is a logical and attractive proposition for seeking a sense of agency; for producing something concrete in the world. Many life-preserving innovations have originated from such dispositions. Still, such world views are rooted in the left hemispheric stance of breaking things apart, embracing categories that are already known, and grabbing them for manipulation for the narrow ends of short-term survival. Hence, the roots need to be uprooted and trimmed before they are replanted — the skills that the world view has cultivated can be very helpful, but they benefit from reorienting to the relations instead of the things — gadgets and solutions — themselves. The workshop uses prompts to evoke the uprooting.

The branches are the epistemological layer where the ways of knowing, imagining, and evaluating legitimacy need to be reconsidered. Once the roots have been replanted, they should feed the new _episteme_. This basis of knowledge arises from trusting intuition, trusting embodied ways of knowing, understanding the limitations of the physicalist positions, and seeing how relations, rather than things themselves, give birth to meaning and purpose. In the technology space, which I have occupied for decades and which I am primarily targeting with this approach, the above ways of attending to the world are rare — they certainly aren’t promoted in education for tech roles or in the day-to-day of working in a technology organisation.

Cultivating systemic views, and imagining alternatives to narratives of forward progress, and acknowledging our place in cosmological contexts, are all examples of how an individual reorientation can take shape, gradually. Beyond that, the notion of disidentifying implies rejecting an identity that one has felt a sense of attachment to. The idea here is to explore, through the workshop approach, which ways of knowing to deemphasise and which to seek, learn, and embrace. Detachment from technological solutionism can be uncomfortable because it might require staying mindful in spaces — such as the workplace — where such a mindset still dominates. As bills still need to be paid and mouths need to be fed, a more thorough detachment and recovery can take years. Welcome to the path I am treading.

Finally, the leaves and flowers are the methodological layer where the ways of doing need to be reevaluated and the story of the singular forward must be questioned to arrive at regenerative outputs. This is where the workshop activity aims to evoke practical ideas about how one can start reorienting one’s technical skill sets and creative energies towards something else than what modernity wants.

Changing the narrative, individually and together

For each of the three layers, workshop participants work ‘together alone’, first writing individual responses to the prompts that inspire them. The individual responses are then shared in a discussion that aims to provoke more thoughts, as participants get to reflect on their input upon hearing from others. Each layer ends in a collective gathering of what the participants consider as the primary takeaways to the next step.

The final step is to collectively intuit an overview of the outputs. Takeaways can be complex and need to be digested to be integrated into everyday practices. The post-workshop reflection requires acknowledging the several conflicting passengers within oneself (‘the bus in us’ approach from Hospicing Modernity) and the uncomfortable feelings it entails. Ultimately, the aim is to practice radical self-reflexivity that has the potential to change the story you tell about who you are. The above speaks for a design for a follow-up workshop to support such work.

Time will tell how this approach works for facilitating the reflective work. There are many details to work out, but anyone who reads this and gets interested, please give me a shout in the comments. I would be more than happy to run a test session!

Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

What a gift it is to share this - thank you Aki. Might also be a curious quest to incorporate air, soil, weather fluctuations as a way to signify the intertwingleness of the eco-system and its non-separation 🏞️.