“Congratulations to whoever invents forests”

Introducing a field kit concept for the work at the ruins

If I've walked into a lot of rooms, over the past fifteen years, and started off talking about climate change, we often ended up talking about something else: the question of what might be worth doing in a time of endings. What is the work that makes sense among the ruins? Most likely, it isn't the work you were doing before the earthquake hit. Out of those conversations, I began to put together a list. — Dougald Hine: At Work in the Ruins, p. 198.

I have previously hinted at the attempt of applying Hine’s list to technologies — an insurmountable task, but nevertheless worth giving a go. A start, at least.

Before we summarise the list and I explain my idea of how to apply it, it is necessary to summarise the premise. In response to the climate change, Hine identifies two paths forward: the ‘big and bright’ lane of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and national programmes that “sets out to limit the damage of climate change through large-scale efforts of management, control, surveillance and innovation, oriented to sustaining a version of existing trajectories of technological progress, economic growth and development.” (P. 19.)

While this path might seem the obvious one, and the only one, it is a product of the engineering mindset. It is illustrated perfectly by the recent tweet by Elon Musk in which he pledged a prize of $100 million to the inventor of the best carbon capture technology.

There is another path, a smaller branching trail, characterised by the cheeky but appropriate response to Musk: “congratulations to whoever invents forests”.

Hine describes the small path as one that “is made by those who seek to build resilience closer to the ground, nurturing capacities and relationships, oriented to a future in which existing trajectories of technological progress, economic growth and development will not be sustained, but where the possibility of a 'world worth living for' nonetheless remains.” (P. 19)

The small path leads to the question of what might be worth doing in a time of endings, not to bet everything on getting to keep everything but to discern, as Hine suggests (p. 198),

what is worth keeping,

what is worth mourning while letting it go,

what is worth recognising for its overinflated value or even harmfulness, and

what can be rediscovered from the past for a future world worth living for.

I want to look at various technologies, using the list as a lens.

Introducing the field kit concept

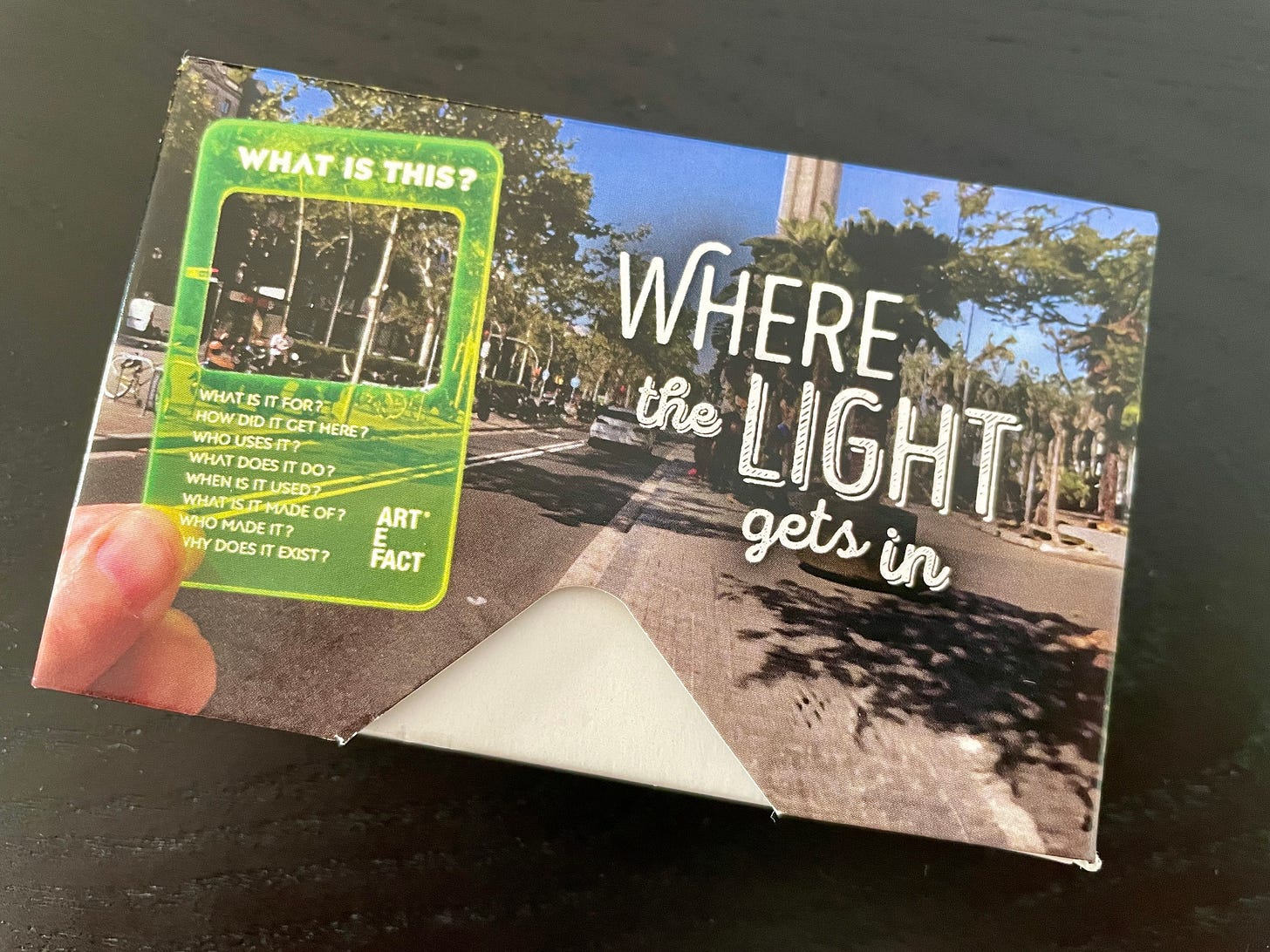

To facilitate thinking around these issues, with a particular focus on technology, I will bring Hine’s thinking into dialogue with work by the design agency Smithery. They have produced various toolkits for thinking about the future, innovation, and design. Smithery’s “regenerative design field kit” Where the light comes in invites us to look at things afresh and ask about their purpose, function, origin, legacy, and so forth — to question things in the world that we tend to take for granted.

In Smithery’s words, the field kit is “a tool designed to expand your perspective as you observe the world around you, reflect on the present, and contemplate potential futures.”

My modest proposal is to adapt the field kit to the hard questions that Hine has put forward.

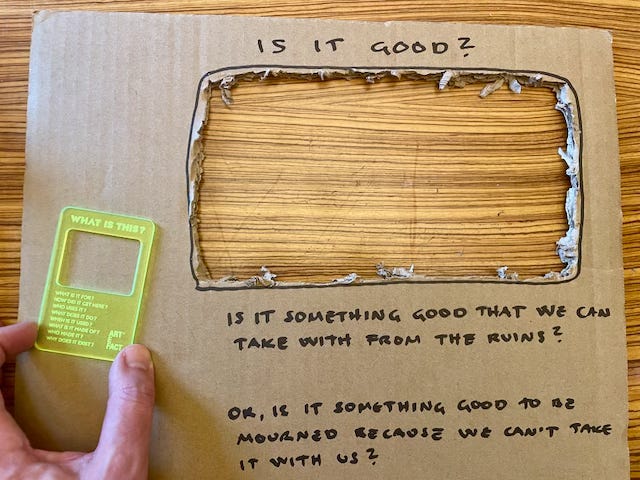

A field kit for the ruins

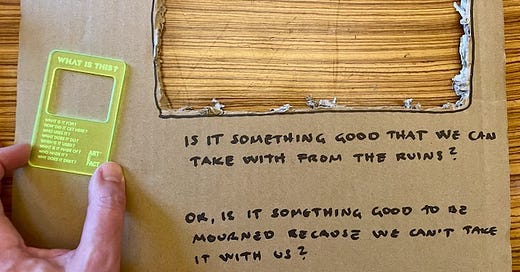

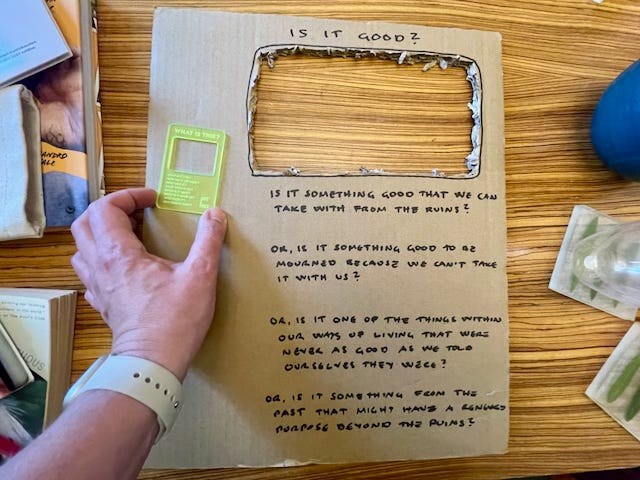

I propose the principle remains the same — pointing the viewer at things in our surroundings and asking “What is this?”. However, the viewer needs a different set of questions, drawn from the list from At work in the ruins as summarised above, and slightly reworded below:

Is it something good that we can take with from the ruins of the world that is ending?

Or, is it something good to be mourned because we can’t take it with us? What is the story about it that we can bring forward, expressing gratitude but letting it go?

Or, is it one of the things within our ways of living that were never as good as we told ourselves they were?

Or, is it one of the dropped threads, something from the past that might have a renewed purpose beyond the ruins; a skill or a practice or a piece of knowledge we can weave into the onward story?

My crude paper prototype, first iteration:

“Where the light shows the technology”

Smithery’s original field kit comes with a deck of question cards that are designed to orient further dialogue around the object, behaviour, or event under analysis.

While the reimagined toolkit can be considered as a version of the original with a narrowed down focus, yet applicable to any observable things to phenomena, my interest is using it to reflect on the various technologies we have brought here to the ruins of this civilisation.

I intend to bring various technological inventions or processes into focus with the viewer, with the aim of being then able to think about their primary, secondary, or even tertiary implications. The supporting cards are still relevant, but continuous use might show that the technology focus benefits from additional or adjusted ones.

The case examples

Undoubtedly, there are technologies or aspects of them that yield trivially obvious conclusions when light is cast upon them in this way. We want to salvage modern medicine, while we probably do not want to salvage profit-seeking medicalisation and big pharma.

We want to salvage science as a way to predict nature’s behaviour, but we don’t want to salvage it as the only way to describe reality and our relationship with it. Therefore, we might need to mourn some forms of science - thank them for what they were but move on.

Consumerism was never as good as we told ourselves, period. The metaphor of natural phenomena as machines can go, too.

We probably want the internet, still, but what about social media? Mobile phones?

These deliberations become more difficult when we find a grey area and/or need to engage with a system-level analysis. For example, when I point it at my microwave oven, to which category does it belong? Is it something to be salvaged — as far as I know, it uses less energy than gas hobs or electric ovens — but has its convenience for our current lifestyle reinforced, for example, the proliferation of ultra-processed foods? If the latter is true, perhaps it isn’t as good an invention as we thought it was.

The point here is not to know all the absolute answers but to use the questions to surface the system-level issues and begin the dialogue about which technologies the workers at the ruins would benefit from. And what falls outside of technology, for us to leave it alone - such as forests.

The work goes on. Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki