How and why to be learnedly ignorant towards technology

The knowledge in not knowing about technology

My previous post was titled “Rehoming technology” and today I will continue unpacking what that might mean. While I am aware that the word ‘rehome’ traditionally refers to animals and pets, I suggest it works as a metaphor with which to grasp something about one’s relationship to technology. As I wrote previously, more important than putting technologies back into their place, so to speak, is to rehome oneself. Not necessarily to your point of physical origin, your birthplace, but to pay more attention to the sense of what home means to you — and actually find home, now or in the near future.

The knowledge in not knowing

The idea of rehoming technology, or rehoming oneself from it, ties into another concept: learned ignorance. It is a concept introduced by the Renaissance theologian Nicholas de Cusa. In an entry to The Encyclopaedia of Renaissance Philosophy, Andrea Fiamma writes:

The expression docta ignorantia (“learned ignorance”) refers to a gnosiological doctrine by Nicholas of Cusa emphasising human structural inability to know the truth. Cusanus states that the human mind is characterised by the fact that it builds relationships between the things, moves itself belonging to quantity and quality and between things opposed to each other. But truth has neither quality nor quantity, and it is the infinite coincidence of the opposites. So, mind because of its finitude is inadequate for knowing the truth.

At the heart of learned ignorance is the idea of knowledge in not knowing.

I propose that the concept might be critical in the process of rehoming of/from technology, or at least a helpful aid throughout it. The notion of learned ignorance stems from our inability to comprehend complex and infinite things absolutely, and recognising that limitation is a step towards any knowing at all. De Cusa’s focal point was God as something so vast that the human mind can only surrender to God, by acknowledging how little can be known about the maximum infinity that God represents. “(T)he foundation for learned ignorance is the fact that absolute truth is beyond our grasp”, de Cusa argued (p. 10 in the 1954 translation by Germain Heron.)

Practical learned ignorance

I am not suggesting an analogy that there is something infinitely complex and maximal about technology; something that can be compared with the complexity of nature (as a manifestation of God). However, I do propose that learned ignorance in the context of the present technology-driven world is about reconciling what we don’t know — or need to know — with what we know about various technologies. It is about letting go of the anxiety that ‘being left behind’ from one instance of technology or the next may induce. There is often deterministic discourse around new technologies that is not helping in relieving such anxiety.

Learned ignorance requires a certain kind of calculated detachment from the noise. For example, practising learned ignorance towards the current AI determinism can help in easing one’s mind into a healthily proportioned attention towards it. One can tell oneself: “No, I don’t need to engage with generative AI because I know there is a value in processing information in the embodied ways that I am in the world, and being content with my limitations, and the convenience of saving some time with the help of such tools is not necessarily a positive trade-off. It can be, sometimes, but I am aware of its shortcomings, too.”

Similar to koans in Zen, learned ignorance is convinced that our default means of reasoning are limited and therefore must be complemented with other ways of knowing.

In “A Non-Occidentalist West? Learned Ignorance and Ecology of Knowledge”, Boaventura de Sousa Santos writes about learned ignorance and other forgotten traditions that are “better prepared than any other to learn from the global South and collaborate with it towards building epistemologies capable of offering credible alternatives” to the predominant ethos of the global North (Santos, p. 114). He promotes ecologies of knowledge and intercultural knowing: “if the truth exists only in the search for truth, knowledge exists only as ecology of knowledge.” (Santos, p. 117)

How to hold the light of learned ignorance

I will return to Santos’ thinking in the next post. Meanwhile, would it be possible to rehome technology with learned ignorance? Take technologies back to a different place, where you cast attention to them in more measured ways?

For me, that would entail nuanced understandings of various technologies and their contexts, balanced with wisdom about their transient and limited capabilities. Ignorance breeds hate, as the saying goes, but learned ignorance breeds equanimity, contentment, and ultimately, wisdom.

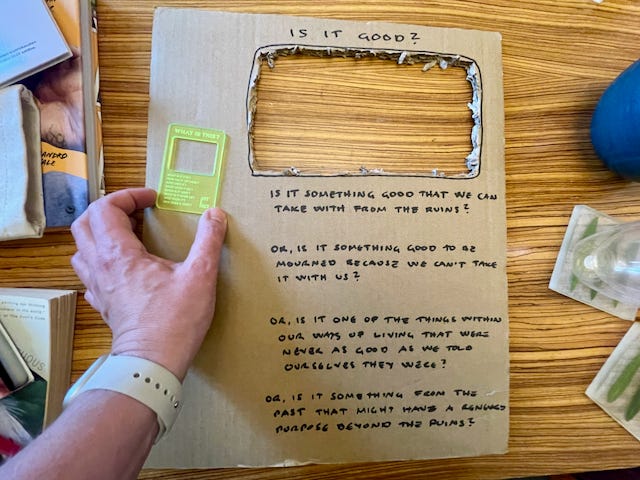

This is where I suggest that “holding the light”, i.e. directing deliberative attention on everyday technologies and asking them fundamental questions (see image below and post here), functions as a practical tool.

To take the notion of rehoming technology more literally, its practices echo ‘homing’ practices with a similar ethos. These include cultivating small communities of living culture, e.g. participating in the regrowth of local ties and a sense of home instead of the displacement that our enchantment with technologies can lead to.

Technologies do have a role in such activities as well, but they need to recede to the background - so that they can always also be easily ignored with a learned attitude.

Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

Aki, I think this is very promising. I might want to write a response, if time allows. The level of hype, and the excitement with which the educational and legal establishments are embracing something they neither understand nor have thought about deeply, is really annoying.

That said, I'm skeptical of the Sousa quote, if only because it is so politically fashionable in the social sciences to genuflect in the direction of "the Global South," a Western cosmopolite (and parochial) concept if there ever was one. Had he said "Cusa can help us understand _________ ," it would have been much better. SO I would have to be convinced.

But never mind that. I think you're on to something. Keep up the good work.

Appreciating the line of enquiry that you're following here, Aki. Some years ago, I published a dialogue with Sajay Samuel, a pupil and close friend of Illich, under the title "Rehoming Society", because in the light of his later writings about "the vernacular" (in Shadow Work), it struck me that "rehoming" was the positive counterpart to the easily misunderstood "deschooling" from Illich's 1970s pamphlets.