Microwave ovens were never as good as we told ourselves they were

Seen through a field kit for workers in the ruins

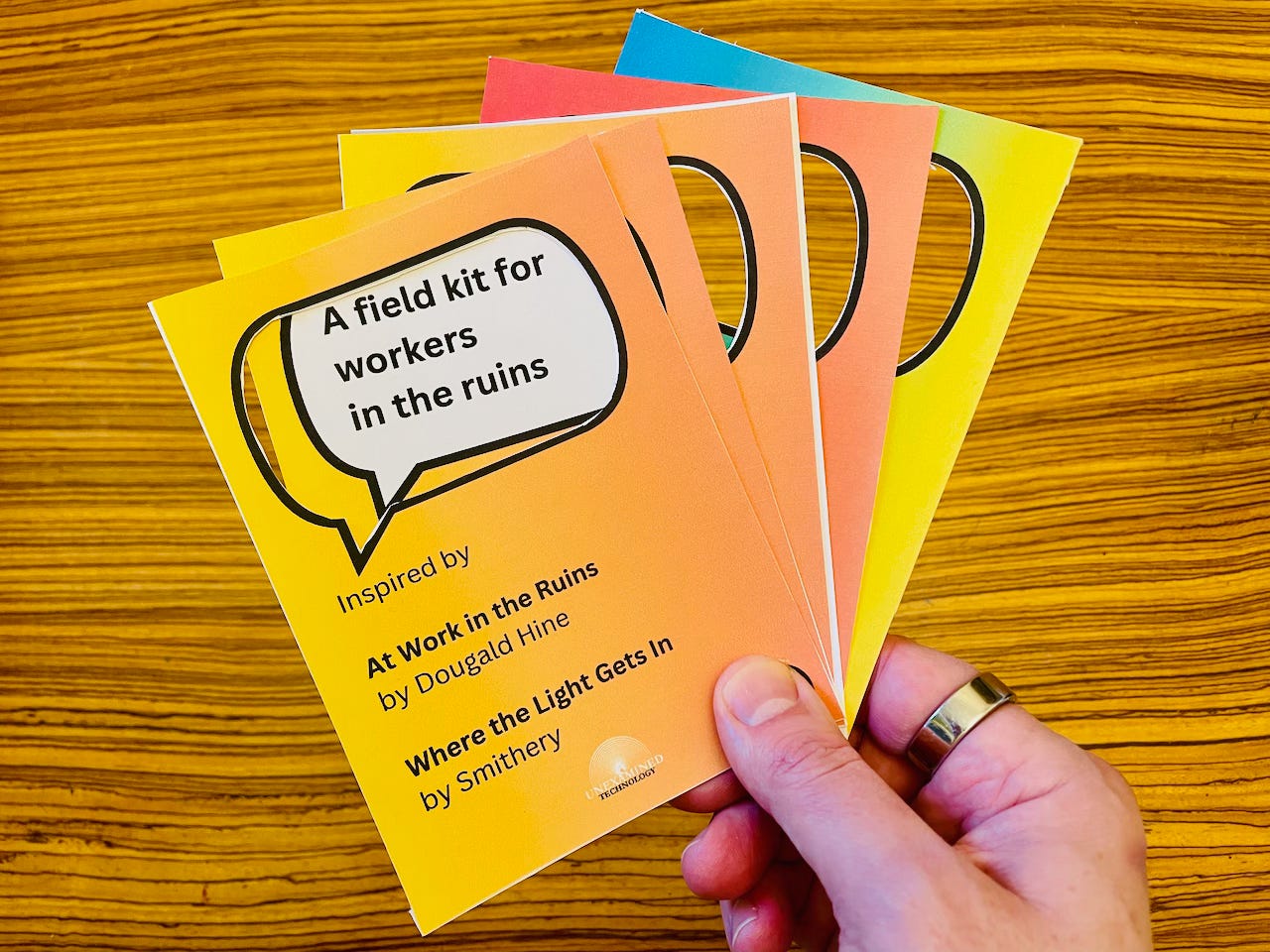

A couple of months ago, I shared the first attempt at combining two approaches to asking questions about phenomena in the world — the design and innovation agency Smithery’s Where The Light Gets In and Dougald Hine’s At Work in the Ruins (now available in paperback!). The purpose was to find a method with which to ask hard questions about the technologies that surround us. Today, I want to share the next iteration of this project, and how I intend to use it going forward.

This kit is designed to foster thinking about “a future in which existing trajectories of technological progress, economic growth and development will not be sustained, but where the possibility of a 'world worth living for' nonetheless remains.” (Dougald Hine in At Work in the Ruins.)

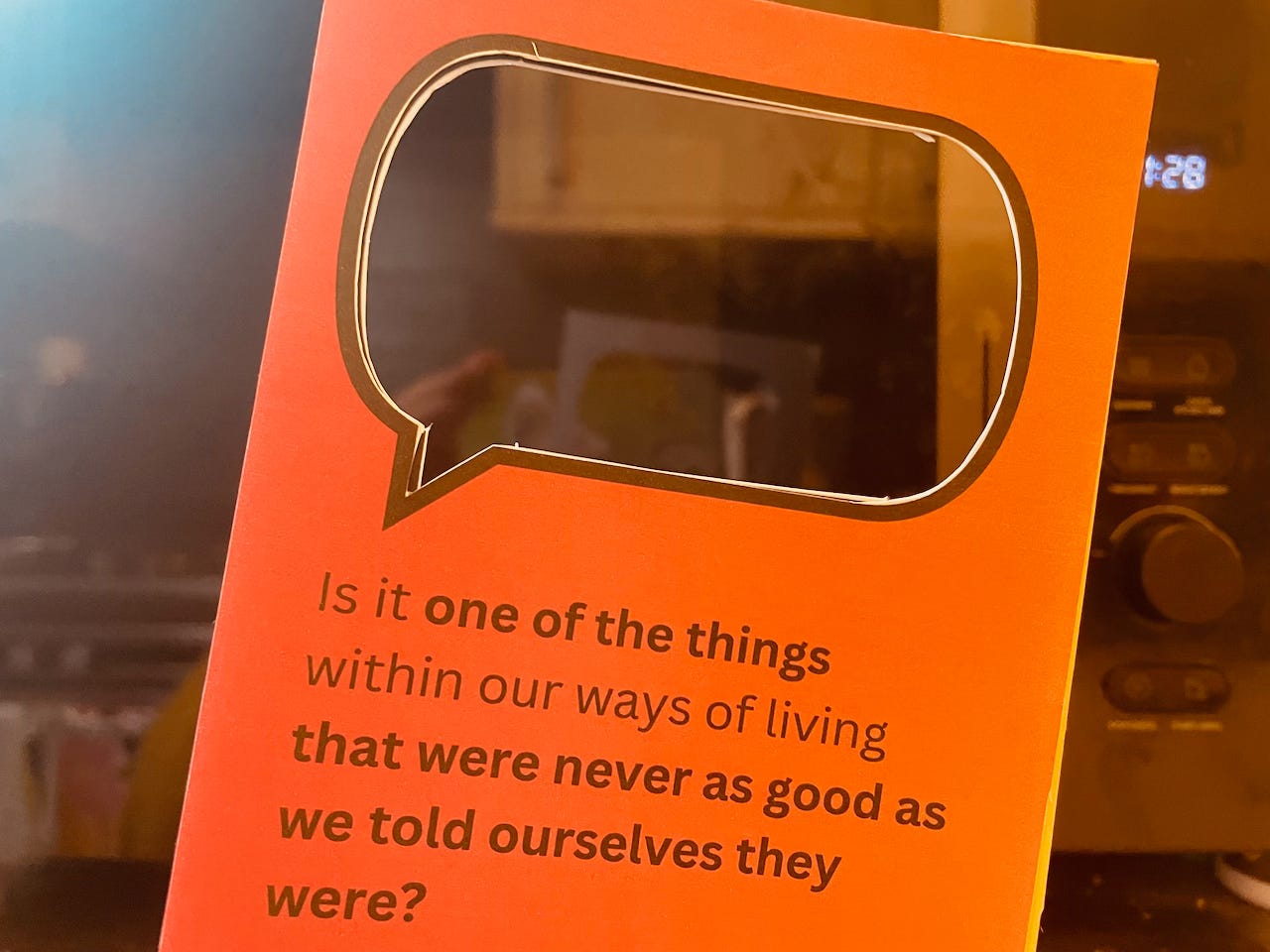

The idea is to point the viewfinder at objects, behaviours, processes, or events and start by asking “What is it?”, and then proceed to the questions in the individual cards to discern what is worth keeping, mourning, letting go, or rediscovering. The fan design of this iteration is an attempt to enable the viewer’s attention to focus on a specific question at a time; to facilitate focused contemplation in the face of what is being looked at.

The kit is designed to inspire the systemic view

In future posts, I intend to share observations I have personally made with the kit: to query various technologies’ role in what might be the end of this era of civilisation. In the earlier post, I pointed the kit at a microwave oven and briefly reflected on how the ovens introduced a convenience into cooking that made them popular. But in so doing, they also accelerated the production and consumption of processed foods and the demand for supply chains that ensure frozen storage temperatures (and the consequent energy demands). Quite possibly, these appliances have had an impact on the decline of cooking skills as well.

A more thorough looking would necessitate in-depth systemic views and research into the secondary and tertiary implications of a phenomenon. Ultimately, this is what I wish the kit to facilitate. On that note, as a way to complement the kit itself with some guidance, in future posts I want to summarise specific methods that support this kind of inquiry, such as the Futures Wheel approach. For now, what follows is a brief excursion into the information necessary to deem the microwave’s fate in the ruins.

Microwave ovens: take it or leave it?

If one searches the Internet about the history of the microwave oven, the typical results are articles with pictures of patent illustrations and debates about who (of the various white men in the discussion) actually invented it, with nostalgic photographs of the early microwave ovens to boot. John M. Osepchuk’s article The history of the microwave oven: A critical review concludes with a typically technology-minded, celebratory statement: “The development of the microwave oven is a wonderful accomplishment and has given a new meaning to the word ‘microwave’”.

The gist of the results from such searches is the following: Microwaves heat the food “inside out”, by vibrating the water molecules in the matter, and this results in heat. The microwave oven would not have come about, post World War II, without wartime research into radar technology. Apparently, the first restaurant-based microwave oven was even called “Radarange”. As tends to happen with technology, over time the ovens transformed from adult-sized towers into the compact boxes we know today. In the process, the technology gets optimised, as did the oven as well, with the introduction of the turntable for more consistent heating, among other features. At the same time, costs came down, and this led to the microwave oven’s breakthrough to American homes in the 1980s and 90s and globally from there.

We seem to be missing the cultural history of the microwave oven, although a fellow Finn, Timo Myllyntaus presents a step to that direction with his 2010 article “The Entry of Males and Machines in the Kitchen: A Social History of the Microwave Oven in Finland”. He refers to the “unexpected broader consequences, including the stimulation of discussion about family values and gender relations”, such as how the ovens might alienate spouses and eradicate family meals, but also have impact on the perceptions of what constitutes ‘real cooking’ and how technologies contribute to ascribing gender and gendered spaces (e.g., the kitchen).

Using the kit to take a stand

So, using the field kit, what is the verdict for microwave ovens? One way to approach this decision is to think about what would happen if microwaves ceased to exist tomorrow. They are more energy-efficient than many other cooking appliances, so likely their disappearance would increase energy consumption. Yet, if the production and distribution of microwaveable (often frozen) foods would be discontinued, that would likely offset the energy costs?

I am not equipped to give definitive answers to such economical questions, nor is the field kit approach in itself meant to be. However, I would argue that using the kit has brought these systemic questions to light; questions about a common household technology that most of us, usually, take for granted and do not pay attention to its broader implications.

Ultimately, beyond enabling the analysis, I also wish the kit to help one to take a stand. So here goes: the damning quality of microwave ovens is their fetishisation of speed and convenience as indications of progress. These appliances, and our adoption of them without too much questioning, persuaded by the marketing of convenience, have contributed to the loss of connection to where our food comes from. Our sense of our food’s origins, and its means of production, has suffered from a long process of obfuscation, and the consumption of microwave-ready foods has played a part in it. Microwave ovens certainly haven’t supported any contemplative — prayer-like, if you will — appreciation of our daily meals.

I’m leaning on the stance that microwave ovens were never as good as we told ourselves they were. Will I stop using my microwave oven? Probably not. But a seed of doubt has been sown into my mind, and when the time for difficult decisions comes, I know what to do.

Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

I love this approach of looking at technology through the lens of the kit, and I agree with many of the conclusions you come to about the microwave. But I want to point out that while it enables and supports the fetishization of speed/efficiency, the microwave also is a way of accessing food for people who do not have the time, the energy, or the physical ability to cook in traditional (more time and labor intensive) ways, whether due to the demands of capitalism, raising a family, disability or illness. This is not to say we shouldn’t abandon the microwave, but rather to keep in mind that when we abandon technologies we need to consider what structures of care and connection need to be put in place to ensure that people aren’t left behind. This is broader than the microwave issue obviously, but in this context- if we abandon the microwave, are we building a network of care so that someone is cooking for and bringing food to the single mother who works two jobs, or to the disabled/chronically ill folks who can’t stand at the stove? We need to abandon many technologies but we also need to build or rebuild the traditions and communities that enable everyone (not just able bodied, well-to-do people) to survive without them. And acknowledge that often the systems that created these technologies are part of the process that marginalized so many people and forced them to depend on such technologies. I know you are aware of these connections, just wanted to make sure they are highlighted in this example/context.