Reaching beyond technology-dominated world views: intuitions and practices

Part 2: Towards spiritual practices

In part 1, I made the argument that educational systems tend to prioritise the technical-empirical world view; a world view that looks down upon anything that cannot be processed with rational thought and expressed in language.

I further argued, following psychiatrist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist’s hemisphere hypothesis, that such a world view is predominantly one of the left hemisphere. It focuses on breaking things down and analysing them as isolated phenomena, often without going beyond other contexts than technology and science itself. It does not begin to know what it cannot know.

This narrow relationship to the world would benefit from trusting in intuition and imagination — something I have previously argued the current, hyped froms of artificial intelligence lack. The complementary view guided by our brain’s right hemisphere consists of seeing phenomena as ever-changing processes and as webs of relations. It does not desperately want to label phenomena and nail them down.

The right hemisphere stance helps in cultivating contextual understanding; in intuiting about the fundamental connectedness of everything. Ultimately, this kind of manoeuvre can lead one to become curious about what lies beyond ordinary everyday existence. It can lead to sophisticated inquiries to one’s self — developments that are typically attributed to spiritual aspirations and practices.

Opening one’s mind to paradigms of thought outside one’s immediate influences and experiences - such as work or school - can be liberating. Adyashanti writes:

What opens inside you when you’re willing to entertain the possibility that things may be different than you thought they were is what I call the “great internal space”: a place where you come to know that you don’t know. This is really the entry point into the end of suffering: when you become conscious of the fact that you don’t really know. I mean that you don’t really know anything—that you don’t really understand the world, you don’t really understand each other, you don’t really understand yourself. - Adyashanti, Falling into grace, p.16

Unexamined Technology is a reader-supported resource to re-examining our relationship to technology. The best way to support my work is by becoming a paid subscriber and sharing it with others. Thank you! -Aki

Letting go of the technological world-view

I suggest that those of us working in technology can benefit from reconsidering what spirituality means. For example, spirituality can be approached as a set of practices and perspectives that help in reaching beyond ordinary, everyday existence.

Yet, you might not feel comfortable with such an idea. Your indoctrination to a technological world-view might explain your reaction. Trusting intuitions where countless threads of past knowledge come together for a moment of wordless insight can seem wishful thinking. This is not surprising — as Iain McGilchrist has observed:

Intuition is also a threat to a world-picture based on administration, adherence to ordained procedures, the power of technology, and a belief in the superiority of abstract mentation over embodied being. - Iain McGilchrist, The Matter with Things, p 723-4.

It is not just psychiarist-turned-philosophers that think so. Albert Einstein trusted his imagination and intuition in creating thought experiments and intuiting ground-breaking conclusions from them. To him, musical and architectonic metaphors were the shapes of intuition and every so often the insights came to him when playing the piano — when engaging with an embodied activity (see The Matter with Things, p 754-5).

Intuitions and practices for a spiritually informed world-view

I ended part 1 by proposing that day-to-day spirituality comes together via two aspects: intuitions and practices. It’s time to elaborate on what I mean by that.

The idea is that the combination of the two, intuitions and practices, is helpful for thinking about what spirituality means for you — and indeed, whether you can honestly characterise yourself as a spiritual person.

This distinction is particularly timely following the increase in people who identify with labels such as ‘spiritual but not religious’ or ‘spiritual but not affiliated’ (SBNA). People typically adopt these labels when they want to distance themselves from organised religions but also atheism, yet not often with any clarity. If you ask a SBNA person what does it mean, it is likely they can’t articulate it very well.

For example, in Northern European largely secular countries - based on my experiences of living in Finland, Denmark, and the UK - people typically have a superficial and uninspiring introduction to religion(s). So did I. What can happen, then, is that when one identifies as atheist, one thinks one knows what one is rejecting, even if one does not. (I am also indebted to

and author Elizabeth Oldfield’s podcasts for this observation.)In my interpretation, anyone identifying themselves as spiritual needs to acknowledge both

a) intuitions that tell them that there exists something greater; something that defies description beyond our everyday existence and

b) practices with which to cultivate and explore those intuitions, in service of searching for a more fully lived life.

Practices create the dialogue with the divine that Lisa Miller refers to in her definition of spirituality I referred to in the first part of this post: ‘spirituality encompasses our relationship and dialogue with this higher presence’. (The Spiritual Child, p. 25.)

Intuition as unconscious intelligence

I have written about intuition when critiquing the hype around generative AI. It’s worth re-visiting what intuition is in the context of spirituality.

The dictionary says that an intuition is “a thing that one knows or considers likely from instinctive feeling rather than conscious reasoning”. Intuitions are not infallible, but the technical-empirical, left hemisphere world view has strongly undermined their value in making sense of the world, largely because intuitions have been considered antithetical to rational analysis.

Philosopher Henri Bergson has described intuitions as inhabiting a subject rather than circling it. The circling from afar implies an objective ‘view from nowhere’ where the witnessing subject — such as a scientist making observations — with all their biases, self-deceptions, and perceptual limitations does not exist. Intuitions about spiritual realms cannot operate like this, they require inhabiting the spiritual. Hence, the practices.

If intuition is unconscious intelligence, we need to embrace the inexpressible, sometimes at the expense of the intellect. Intuitions are by definition ephemeral and subjective, but they have an underlying common element: what they point to — an undercurrent, something mentioned in definitions of spirituality, such as nature, divinity, and the universe.

Yet as Bergson says, without intellect, intuition would be ‘mere’ instinct, something that most animals live by. Intuition, therefore, serves wisdom that is accumulated through time and through relations. Iain McGilchrist suggests that intuitions have a historical dimension, that they are layered like a river bed. He writes:

And the layers may differ in nature. Thus it is possible to speak of our ‘now intuitive’ belief in the mechanistic world-picture, but this is a recent accretion on top of much older intuitions about the world as living, organic, responsive, whole - intuitions that I believe science may be in the process of validating once more. - Iain McGilchrist, The Matter with Things, p 741-2.

Embracing the sense of the sacred or, in other words, opening oneself to spiritual matters, presents a way to cultivate intuitions that draw from the deeper sediments of history.

Flipping the script

For now, I will keep unpacking what spirituality can mean for a technologically oriented person. Making this count - i.e. persuading a rationally oriented mind - might be a big ask, no less than what scholar Jeffrey Kripal has described as ‘the flip’ — something that I covered when writing about critical technical awakenings. Kripal writes about several cases of prominent scientists and medical professionals who have gone through a conversion in their world view from materialistic to a more “cosmic outlook in which mind or consciousness is primary” (Jeffrey T. Kripal, The Flip, p 58).

Typically, the flip follows a seismic personal event, such as a loss of a loved one, separation from a partner, or similar. Yet, it does not have to be as dramatic as that. The opening can be more gradual: a step into self-inquiry that surfaces intuitions, and continuing that dialogue with practices that cultivate it.

As a combination of intuitions and practices, spirituality is intentional and guiding rather than reduced to routines. Yet, conducting spiritual inquiries so that they become adopted as practices is about creating habits. That is fine as long as your heart is in it.

Against dogmatism

The intuitions and practices you cultivate may belong to any organised religion, but they may just as well originate from indigenous cultures, esoteric traditions, or mystical contexts. For example, studying myths (religious or otherwise) and understanding them as narratives about eternal truths and universal meanings, rather than as fantastical stories from the ancient past, can be eye-opening.

I refer to intuitions rather than beliefs for an important reason. Organised religions have a tendency, by referring to holy scriptures, to instil beliefs that become learned, unchangeable dogmas rather than intuitions that arise from within. Rather than clinging into dogmatic beliefs, spirituality, when it takes the form of Vedantic traditions, for example, is about leaving beliefs behind.

Yet, John Gray has argued in his book Seven types of atheism that the notion of religion as a matter of belief only applies to Christianity. Most other religions do not posit belief as central. For example, vedantic traditions promote a view where through self-inquiry one strips away all beliefs instead of adopting or clinging to them. Prioritising beliefs also means that someone who declares themselves a non-believer, and consequently an atheist, lumps all religions together. (Rather, most religions are, in fact, atheist in that they do not define a single creator-god, i.e. subscribe to a theist view.)

Regardless, there exists various belief-systems in the world that are as capable of dogmatism as certain churches within Christianity. As

writes in her book Enchanted Life,[M]any religions, in their dogmatic adherence to one particular way of seeing the world, relieve us of possibility and so fetter our imaginations. Wonder and awe, they tell us, can be turned only in one direction: never onto what is ‘worldly’, but always in the direction of God. - Enchanted Life, p. 26.

As I referred to above, academic institutions are equally well-equipped to indoctrinate students to believe that a certain intellectual way of explaining the world is all there is. This echoes what prominent physicists believed about Newtonian physics a century ago, i.e. that the field was essentially ‘done’ (before the discovery of quantum particles).

An irrational example of a similar dogmatic belief? Look no further than creationists, who are fighting to remove books about evolution from school curricula. Often such clinging to beliefs is a result of a standpoint that does not understand its limitations.

An ecology of practices

Following John Vervaeke’s approach, the term ‘ecology’ underlines the interdependency of a set of practices that feed into each other. I suggest everyone needs to find their eclectic mix where intuitions and practices meet. Thus far, we have been laying some groundwork in this newsletter - I hope to continue pointing you to practices that I have found useful. Some of them will deserve a post of their own, some of them I will refer to via the readings, videos, etc, I recommend. In all of this, I am very much a student myself; I claim only intermediate experience at best.

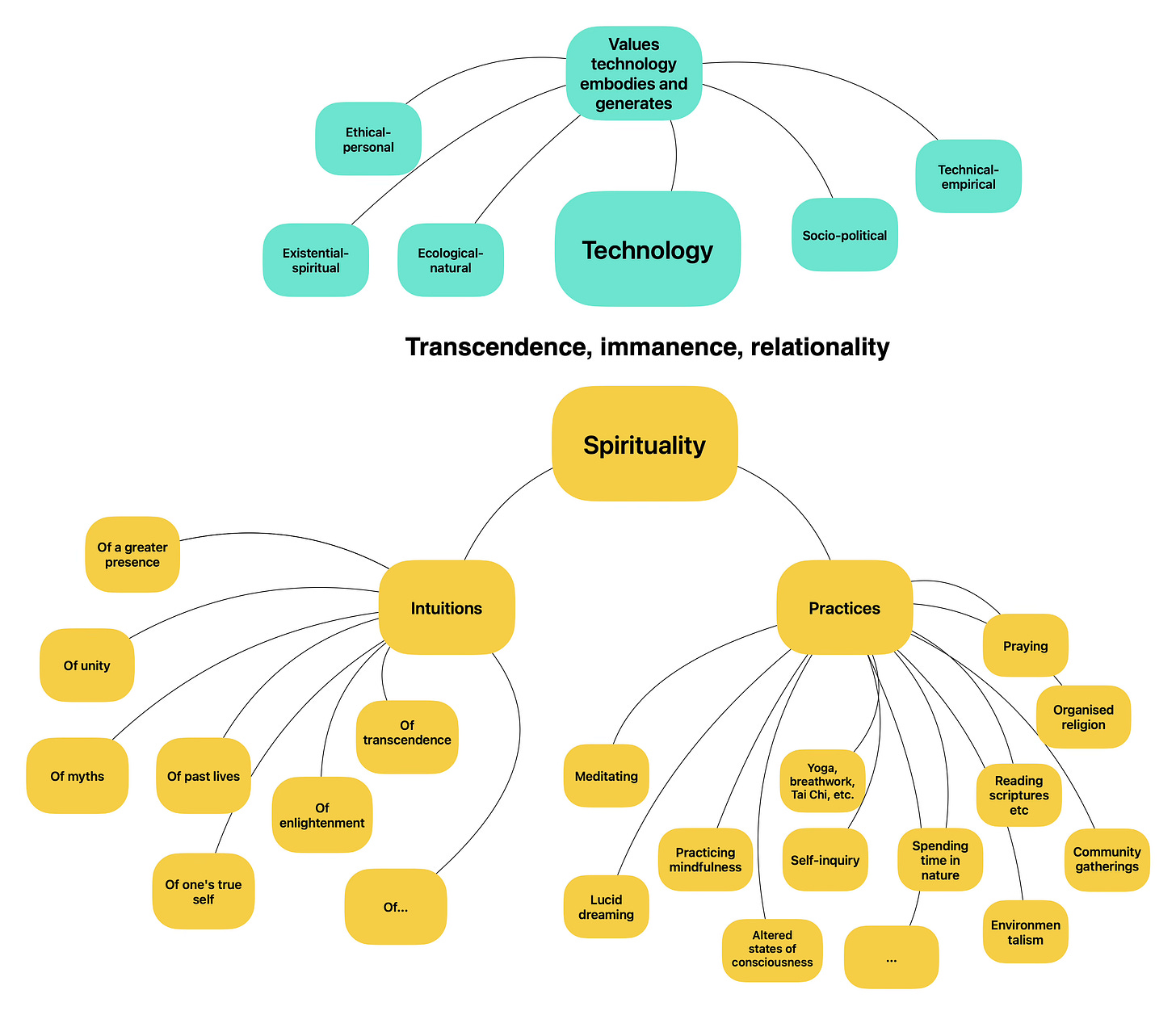

I will leave you with an evolving mind map that organises some of the above thinking and illustrates the various domains of inquiry, practice, and concepts that I will be covering in future posts. (The scholars Stephen Perine and Franc Feng do something similar in the article I cited in part 1, but unfortunately, I find their mapping rather inaccessible.)

The map is an attempt to build bridges between our attention to technology and spirituality — attention, which, while divided, would benefit from not being entirely divorced. Please note that the map is very much a work-in-progress that I expect to revise along the way. I will return to it in the near future, including explaining how transcendence, immanence, and relationally figure as mediators between technology and spirituality.

Thank you for reading. As always, I leave you with a piece of contemplative algorithmic art:

With love and kindness,

Aki