In the previous post, I wrote about the cruelty of techno-optimism and proposed radical hope and hard imagination as alternative dispositions when thinking about the future and the role of technology as part of it. But how to take such stances into practice when working with technologies? How to think about evaluating technologies or ideas for future technologies through the lens of radical hope?

Fortunately, the groundwork exists. It comes in the form of approaches to technologies’ role in economical models that are not founded on the notion of infinite growth. Such models tend to be categorised under titles such as degrowth or post-growth. For thinking about technologies’ role in post-growth societies, scholar Andrea Vetter’s “Matrix of Convivial Technology” is inspiring in its practicality. The matrix is designed to engage its users into dialogue about “which technologies would be appropriate for a degrowth society”. Vetter explains that “the concepts of convivial tools and radical technology emphasize the importance of the social that constructs and is constructed by technology.” (Vetter 2018, p. 1780.)

It is fitting that the inspiration for the model comes from Ivan Illich’s concept of conviviality. The word originates from the Latin con vivere, to live together. In Tools for Conviviality, originally from 1973, Illich writes:

I choose the term "conviviality" to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment; and this in contrast with the conditioned response of persons to the demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment. I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value. I believe that, in any society, as conviviality is reduced below a certain level, no amount of industrial productivity can effectively satisfy the needs it creates among society's members.

The last sentence actually articulates the same impasse that Lauren Berlant does with cruel optimism — that the promises about a better future are hindered by the very ways that the society requires its citizens to work towards them. In the quest for convivial technologies, we need to be aware that we do not impose the same impasse.

One way out of this dead end is shifting into a different economic system. To make any progress towards conviviality, it is critical that there is alignment with the alternatives to the current hegemony of growth, whether one prefers one term over another, i.e. ‘de-growth’ or ‘post-growth’.

Yet, the skeptic might ask, why do we need convivial technologies; aren’t the current technologies convivial enough? Today’s communication technologies connect people across the globe, housing and transport solutions bring people together, and so on? My argument is that such skepticism is based on blindness, or ignorance, to how the technologies that have led us here have supported not only the afore-mentioned individualism, but also singular narratives about progress and wealth. As a by-product, the erosion of conviviality and belief in growth without limits has led to an ever-increasing consumption of energy that will not be sustainable for long any more. Besides the unsustainable consumption, if our technologies keep impacting our abilities to live together negatively, they also contribute to the increase in toxic individuality and tribalism.

The matrix as a design tool

In her research, Andrea Vetter set out to produce a tool that would “help developers of potentially convivial technologies to self-asses their products”. Consequently, she sought to popularise the idea of convivial technologies and position the matrix into historical contexts with past movements similar in spirit, such as the Centre for Alternative Technologies founded in Wales in 1973.

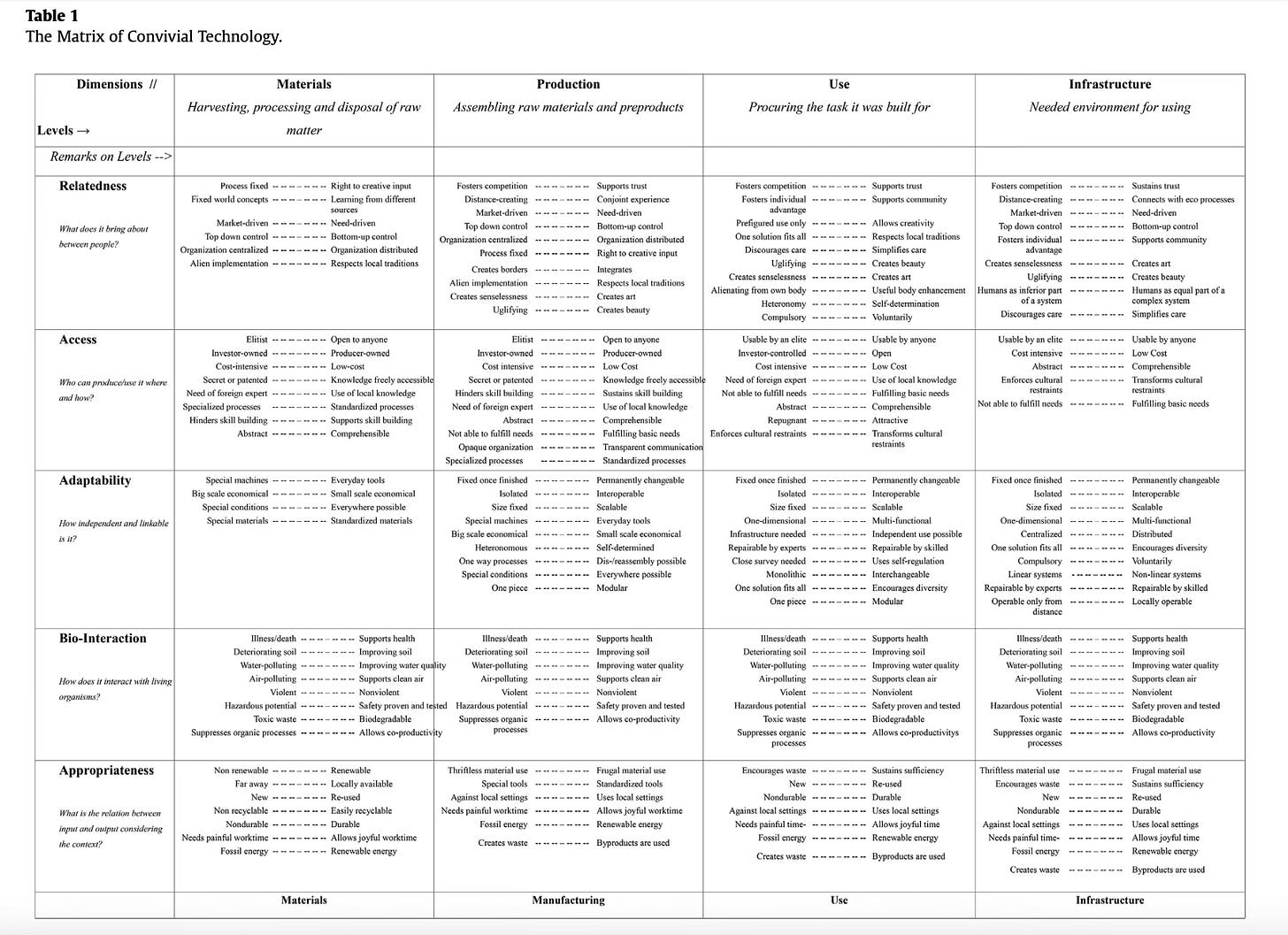

The matrix provides detailed discussion and decision points in the form of the various dimensions, levels, and axes it presents. The dimensions are of an overarching nature and have echoes of responsible innovation frameworks. Three of them: Access, Adaptability, and Appropriateness, can be found in responsible innovation frameworks. Respectively, these have to do with who can produce the technology, where, and how (access), how independent versus embedded is the technology (adaptability), and contextual questions such as whether the technology creates waste and how the waste is dealt with (appropriateness).

The remaining two dimensions, Relatedness and Bio-Interaction, are results of the particular focus on conviviality and degrowth. Relatedness refers to what the technology “brings about between people”, and bio-interaction is about the technology’s interactions with living organisms. As a whole, the five “dimensions propose an ideal of degrowth technologies that can serve as a focal point for the question of which technologies would be appropriate for a degrowth society.” (p. 1785.)

Importantly, the matrix adds depth to the inquiry by suggesting that each dimension needs to be explored via four levels: how materials are harvested, processed, and disposed of; how production is organised; what kind of use the technology fosters; and what is the infrastructure required for the use. For example, in terms of relatedness, is the production process founded on needs of the people or of the market, or in terms of access, is the use of the technology investor-controlled or open?

In terms of the levels in the matrix, the design decisions toward degrowth would become tangible in how the technology under scrutiny skews towards a combination of elements. For example: is it locally operable and low cost (infrastructure), is it interoperable and voluntary (use), does it foster skill building and respect for local traditions (production), and is it founded on biodegradable and small scale (materials)?

Approached this way, the matrix can be employed as a set of constraints for ideating convivial technologies — at least on paper. To take it beyond the paper, the tough practical decisions would come when the convivial design qualities would need to be championed in real-world contexts, in order for them to be actually implemented without too many compromises. This, the execution, is the real challenge, as always.

Barriers to conviviality

Ivan Illich’s original thinking on conviviality sheds light on why such attempts at execution and recovery will be hard. He provides another concept that resonates in today’s technosphere: “radical monopoly”.

By "radical monopoly" I mean the dominance of one type of product rather than the dominance of one brand. I speak about radical monopoly when one industrial production process exercises an exclusive control over the satisfaction of a pressing need, and excludes nonindustrial activities from competition. (Tools for Conviviality, p. 52)

Illich writes how cars have radically monopolised traffic and made contemporary cities into their image, how funeral homes have monopolised burial rites and schools have monopolised education. He points out how in such processes, often expressed as verbs, the acts of doing, become institutionalised and therefore described by nouns. ‘Education’, a noun, monopolises ‘learning’, a verb. Illich observes that such shifts in language have been among the subtle workings in how industrialised societies have brushed conviviality aside. He elaborates:

The establishment of radical monopoly happens when people give up their native ability to do what they can do for themselves and for each other, in exchange for something "better" that can be done for them only by a major tool. (Tools for Conviviality, p. 54)

Institutions have replaced personal responses, the verbs, by making us increasingly dependent on services that create “radical scarcity of personal-as opposed to institutional-service” (p. 54). Today, it looks like we are witnessing the radical monopoly of AI being born, and the conviviality of the various flavours of AI seems questionable at best. As it happens, Professor André Reichel has applied the matrix and written about AI as convivial technology (in 2019, before the recent LLM hype). He summarises: “Artificial Intelligence research needs to focus on enriching people’s relation to each other, empower them to organise their life beyond the market, and assist in the transformation towards sustainability.” When employed in such a way, the technology would support conviviality rather than erode it, but examples are becoming few.

To conclude, if the technology is harnessed for pure productivity in the name of economic growth — rather than for use cases which seek mutually respectful co-existence and relieving suffering — it erodes conviviality. Or, as Illich suggested, when we lose (and have lost!) our native ability to do something useful for ourselves and our community, and have to rely on a tool that monopolises that ability.

The systemic challenge would be to sketch out a vision for transforming technology development and its outputs into a convivial frame. As always with forward-looking methods, this would require taking external developments into account. These vectors impacting the outlook of the timeline might just be a set of four inconvenient but imperative Ds: de-colonialise, de-grow, de-intensify, and de-technologise.

I am all for AI for medicine discovery, for example, but even then, in the current climate, it would likely happen in the context of big pharma and medicalisation — developments that have abandoned medicine’s origins in conviviality to profit-seeking operations within capitalism. Especially given the recent and future crises affecting supply chains, returning to local medicine production would recover some conviviality of the past whilst leveraging the innovations of today.

The five Ps for conviviality

The above ties into what sociologists such as Hartmut Rosa has discussed as intensification, an imposition of contemporary life — and its economies and technologies — that proposes that we constantly need to extend our reach within the world because otherwise we would be ‘left behind’. Such intensification, taking place in the context of the type of alienation that critics of capitalism have expressed for over a century now, stems from what has been ‘gained’: e.g., technologies, freedom of movement, specialisation, increasing number of societal subsystems governed by bureaucracy, etc. In sum, these developments amount to a general pace of life that implies that other rhythms of living are impossible. They are deemed impossible in the public imagination, because they do not produce growth. As if there could not be wealth that is not measured by money or a scale of global proportions.

Yet, the intensification stems at least equally much from what we have largely lost than what we have gained. Paul Kingsnorth has put forward an interpretation of the lost; the four Ps: people, place, prayer, and the past. Re-engaging with these four aspects of life suggests an antidote to alienation and intensification, a reigniting of relationships between oneself and the world instead of the overbearing silence that disenchantment from them brings about.

The starting point for rediscovered conviviality, as I understand it, would be to ask what each of the Ps means for you, personally. I hasten to add another P, or D, to the mix: post-growth, the idea of a societal system that lets go of the absurd idea of infinite growth on a planet of finite energy resources. In doing so, a post-growth world would at have a chance to provide for our grandchildren and their children a decent quality of living, regardless of which part of the planet they inhabit. While the fifth P might come about from the first four Ps, conviviality would be their sum total.

Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki