Today’s post is different in that it is a slightly edited version of my proposal for a PhD study. I was planning to apply to study part-time for a (second) doctorate through the end of 2024, but ultimately decided to delay the application, mostly for funding-related reasons. Nevertheless, the project described below remains in my plans and will only crystallise through the present year.

Some of you might ask, fairly, why an academic study? My answer is that while I am exploring similar topics in this publication, the academic context would give me a structure where deadlines are set by someone else than myself. . It would also open a way for me to engage with a research community (Science and Technology Studies) that I feel does important work. The title of the post is the working title from the proposal, with “translating neuroscience and marginalised knowledge for a new approach to technology design and policy” as the subtitle.

Spoiler alert — I have a confession to make: even if a serious academic study should not anticipate what the outputs will be, I’m pretty confident that most innovation efforts with technology should focus on crisis management and resolution, in addition to empowering small communities to produce food, medicine, and shelter with locally grown resources. These are things that modernity has taught us to consider as the opposites of progress. But we should know better than modernity.

Thank you for reading. Please also look out for a reader survey next week — I’d love to hear your thoughts about how to improve the publication!

With love and kindness,

Aki

Introduction: the predicament

What is the matter with contemporary technology design and development, given that its forward progress has led the planet to the brink of a climate catastrophe and arguably contributed to other socio-economic predicaments, such as the mental health epidemic? How can it be that the current civilisation is the most technologically advanced, yet it is living through a ‘polycrisis’, i.e. “the causal entanglement of crises in multiple global systems in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects” (Lawrence et al 2024)?

I suggest that it is critical for the science and technology research community to suggest alternative approaches to dealing with the predicaments of our time — otherwise the trajectory of innovation will continue on a path of technological determinism, with well-intended but futile attempts at infusing responsibility and ethics into the innovation process. This trajectory is not one of resilient, healthy, and environmentally sustainable outcomes. It is important to

surface research evidence that links the systemic consequences of technology innovation to the emergence of the polycrisis,

to identify and question the predominant drivers for technology innovation within modernity, and

propose interventions toward more desirable futures.

To map alternate trajectories in the context of technology innovation, I propose a PhD study that puts forward several questions: How would technology development change, if it was inspired by different modes of attention and ways of being in the world, as evidenced by neuroscience? What if technologists’ attention would be shifted to another body of literature and insight, previously ignored because it has not aligned with the hyper-rational stance that the typical curricula of engineering, computer science, and innovation demonstrate? What would that alternative body of knowledge look like? Finally, where are the limits of applying neuroscientific perspectives to technology innovation as human activity, and what do those limits look like?

The challenges to innovation as we know it

While the innovation and design communities have come up with approaches that champion responsibility and sustainability in innovation, it appears that these methods still face a multitude of challenges when applied into practice and their impact is difficult to measure (see, e.g., Frahm et al. 2022, Li et al. 2023, Hussain et al. 2022). Moreover, ethical approaches to technology development, e.g., with AI, nevertheless tend to foster a techno-solutionist mindset (see Metcalf et al. 2019, Wong et al. 2023) rather than a virtuous, contemplative starting point. To summarise, both the engineering, computer science, and design communities have been looking for alternative approaches — i.e. the recognition for change is there, in particular with the rise of AI — but the results have been mixed.

Why is this? I suggest that the issue with the existing approaches is that they tend to lead their practitioners and decision-makers into addressing problems with thinking that is similar to what gave birth to the crises: thinking that privileges new technology, innovation, and economic growth as virtues in themselves. The underlying issue seems to be in how innovators and technologists attend to the world; how they tend to isolate technology and its implications rather than contextualise them, despite approaches such as responsible innovation and value-sensitive design (Friedman 2004). Here I propose that careful translation – wary of colonialist interests – of marginalised bodies of knowledge can point the way for resilient innovation practices that arise from alternative dispositions to the world. Besides spiritual and wisdom traditions, such bodies of knowledge include indigenous and gender-sensitive perspectives.

Inspiration

One way to understand the broad term ‘technology’ is to see it as a host of applications of scientific findings and principles into building devices, tools, techniques, and processes. However, this premise has not prevented the emergence of multiple planetary crises, rather the opposite. Consequently, the proposed study aims to shed light on the epistemological groundings of technology innovation as applied science.

The phenomenon can be studied from a Science and Technology Studies (STS) perspective, complemented with neuroscience, and with a philosophical emphasis. My study draws from philosophy and neuroscience to propose how technology development can be approached with alternative dispositions that have dominated modernity. In neuroscientific terms, this translates to different modes of attention, i.e. different ways of being in the world. The key lens for the investigation is philosopher and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist's hemisphere hypothesis based on a body of literature in neuroscience and beyond. According to McGilchrist's analysis, our brains pay attention to the world in two distinct ways. He shows how for both humans and animals it has been necessary to simultaneously retain a focused attention on objects in the world, such as tools or food, while maintaining a holistic alertness to the broader contexts, such as the surroundings and hazards. The left hemisphere of the brain serves the former, narrow focus, and the right hemisphere the latter.

The hypothesis for my study is that, in the decades-long lead up to the polycrisis, technology developers and adopters – driven with help from the deterministic rhetoric with which technology is often promoted – have privileged the grasping, manipulative, and literal stance of the left hemisphere. If the hemisphere hypothesis can contribute to our understanding of the origins of the polycrisis, what would a more balanced, or right-hemisphere-leaning attention to technology innovation look like?

McGilchrist traces the roots of the current left hemisphere dominance to Ancient Greece and the reductionist foundations of Western science. Technology development has leveraged the resulting scientific method that, while enabling inquiry to a wide range of natural phenomena and how to exploit them for human purposes, simultaneously closes several other paths of inquiry. The ones excluded include indigenous knowledge, wisdom traditions, and political movements that emphasise the importance of relations and connectedness — i.e. right-hemispheric leanings — as grounds of being and inquiry. Instead, we’ve lived with the isolating and overtly analytic approaches that modern scientific paradigms have preferred, in the service of modernity and its project of infinite growth and human exceptionalism. Some thinkers have proposed that the next paradigm shift in science will come from the reconciliation of the Western method with indigenous and Eastern perspectives, which would reflect McGilchrist’s argument.

Translation and application

To deal with the polycrisis, our activities around technology might benefit from adopting the holistic and reconstructive stance of the right hemisphere. In practice, in the technology innovation contexts, this would mean embracing systemic thinking on the macro-level, and exploring spiritually aware, regenerative approaches on the micro-level. Engaging innovators into such a transformation will be a difficult task because the left hemisphere leads us to recognise only what is already familiar and cannot see its limitations — also regarding where resources are invested, what type of research is funded, and according to what economic model. Yet, research-based insights about the possible shapes of this transformation via alternate routes are necessary, and the study aims to contribute to such debates.

Part of the research is to seek and present evidence for this hypothesis in the context of the role that technology plays in our society — with the current rapid rise of Artificial Intelligence as a particular focus of critique. The AI tools that trend analysts claim are disrupting every industry in the upcoming years (Future Today Institute 2024) appear to represent an epitome of left-brain emphasis. Therefore, my study will aim to gather evidence that new, radically different convictions and pursuits of knowledge are needed for technology development to align with non-extractive, 'metamodern' thinking that supports planetary flourishing.

Research questions

Is there research evidence that links the systemic consequences of technology innovation to the polycrisis and if so, what does it mean for technology and innovation policies?

If the predominant drivers for technology innovation – growth, productivity, etc – remain the same, what kinds of systemic developments can be anticipated?

What can neuroscientific findings about our ways of being in the world bring to the critiques of responsible innovation and technology development?

What types of marginalised knowledge (e.g. indigenous, mythical, spiritual) are missing from the efforts in responsible technology innovation?

What, consequently, are the alternatives to materialist and reductionist perspectives to technology-led innovation?

With the current rapid growth of Artificial Intelligence across several sectors, how do the current RI approaches need to re-invent themselves in light of the above?

Methodology

To address the research questions, I will employ a methodology of close reading of spiritual and wisdom literature, complemented with a review of the evidence for modern technologies’ role in today’s predicaments — the climate and mental health crises in particular.

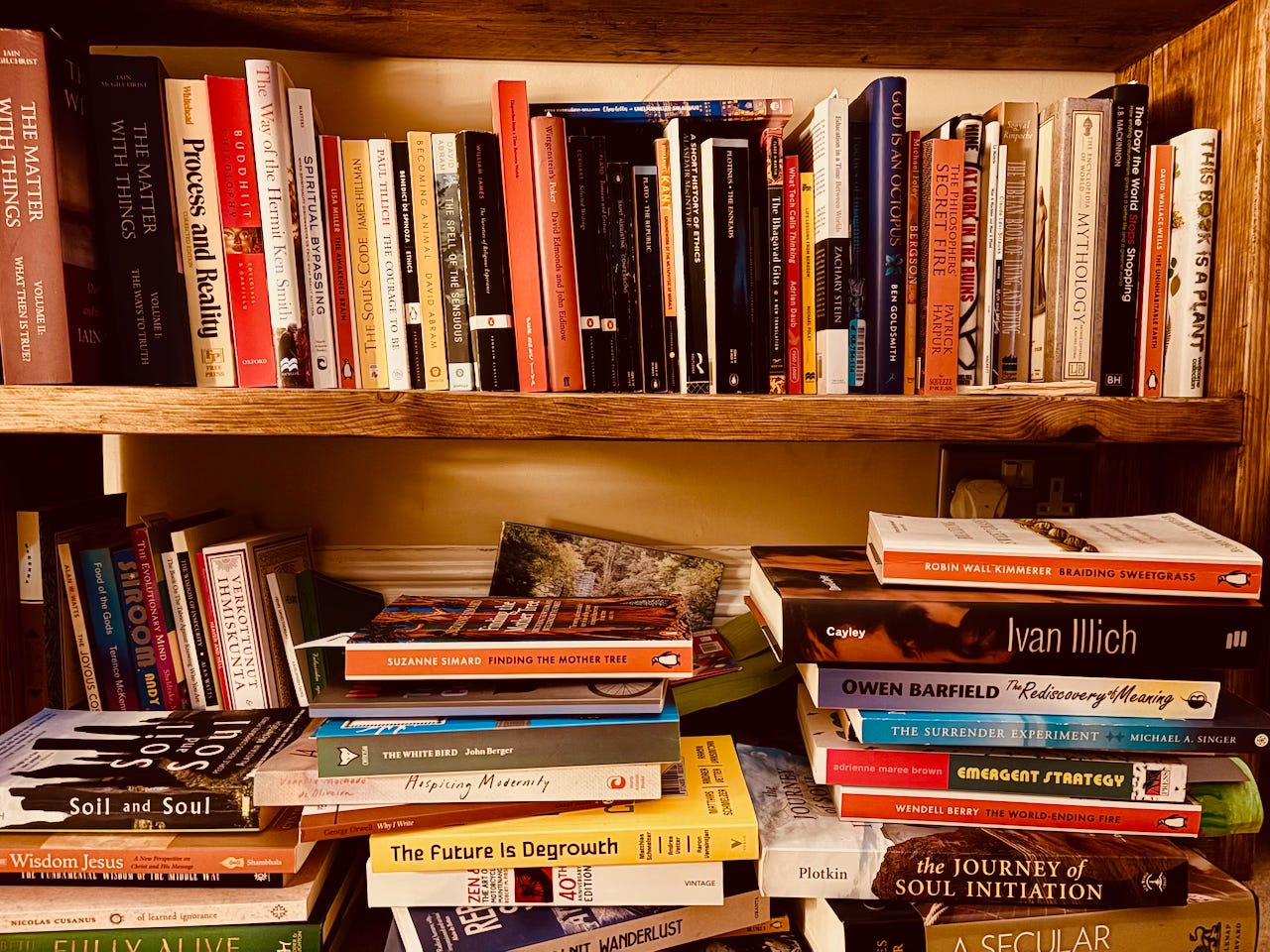

Besides the hemisphere hypothesis, the philosophical grounding of the work will draw inspiration from concepts such as hospicing modernity (Oliveira 2021), critical technical practice (Agre 1997), The Machine (Kingsnorth 2023), planet-centric design (Huber 2021), degrowth (Schmelzer et al. 2022), spirituality for well-being (Miller 2022), spiritual caretaking in technology development (Van Noppen 2021), virtue ethics (Vallor 2016), indigenous knowledge (Yunkaporta 2023), among others. This diverse body of literature represents a cross-section of alternative perspectives to the prevailing ethos of modernity, and in the study it constitutes a multi-faceted lens through which to question the foundations of technological innovation and the economical incentives that drive it. In the research process, some of the above viewpoints are likely to become more prominent than others — the literature mentioned here functions as a starting point, and I am eager to add perspectives from, e.g., gender studies and feminism as notions such as situated knowledge (Haraway 1988) align with the hemisphere hypothesis.

By combining the findings with personal experience from over a 20-year-long career in technology, I aim to synthesise a framework that proposes alternative starting points for technology development and policy.

References

Philip Agre (1997) Toward a Critical Technical Practice: Lessons Learned in Trying to Reform AI. https://www.pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/agre/critical.html

Frahm, N., Doezema, T ., & Pfotenhauer, S. (2022). Fixing Technology with Society: The Coproduction of Democratic Deficits and Responsible Innovation at the OECD and the European Commission. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 47(1), 174-216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243921999100

Friedman, B. (2004). Value Sensitive Design. In W. S. Bainbridge (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human-computer Interaction (pp. 769–774). Berkshire Publishing Group. https://old.vsdesign.org/publications/pdf/friedman04vsd_encyclopedia.pdf

Future Today Institute (2024) 2024 Tech Trends Report. https://futuretodayinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/TR2024_Full-Report_FINAL_LINKED.pdf

Haraway, Donna (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 575-599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Huber, Samuel. (2021)”What is planet-centric design? https://samuelhuber.medium.com/what-is-planet-centric-design-8d1754b52fba

Hussain, W., Perera, H., Whittle, J. Nurwidyantoro, A., Hoda, R., Ara Shams, R., and Oliver, G. (2022) Human Values in Software Engineering: Contrasting Case Studies of Practice. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, VOL. 48, NO. 5, MAY 2022

Kingsnorth, Paul (2023) The Tale of the Machine. https://paulkingsnorth.substack.com/p/the-tale-of-the-machine

McGilchrist, Iain (2009) The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press.

McGilchrist, Iain (2023) The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World. Perspectiva.

Lawrence M, Homer-Dixon T , Janzwood S, Rockstöm J, Renn O, Donges JF (2024). Global polycrisis: the causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement. Global Sustainability 7, e6, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2024.1

Li, W.; Yigitcanlar, T .; Browne, W.; Nili, A. (2023) The Making of Responsible Innovation and Technology: An Overview and Framework. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1996–2039. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/smartcities6040093

Metcalf, J., Moss, E., & boyd, danah (2019). Owning Ethics: Corporate Logics, Silicon Valley, and the Institutionalization of Ethics. Social Research: An International Quarterly 86(2), 449-476. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Owning-Ethics-PDF-version-2.pdf

Miller, Lisa (2022) The Awakened Brain: The Psychology of Spirituality. Penguin.

Oliveira, Vanessa Machado de (2021) Hospicing Modernity: Parting with Harmful Ways of Living. North Atlantic Books.

Schmelzer, M, Vetter, A. & Vansintjan, A. (2022) The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism. Verso.

Yunkaporta, Tyson (2023) Sand T alk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. T ext Publishing.

Van Noppen, Aden (2021) Creating Technology Worthy of the Human Spirit. Journal of Social Computing, 2021, 2(4): 309-322. https://doi.org/10.23919/JSC.2021.0024

Vallor, Shannon (2016) Technology and the Virtues. A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting. Oxford University Press.

Wong, Richmond Y ., Madaio, Michael A., and Merrill, Nick (2023) Seeing Like a T oolkit: How Toolkits Envision the Work of AI Ethics. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 7, CSCW1, Article 145 (April 2023), 27 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579621

this is fascinating! would recommend “designing for the pluriverse” if you haven’t already read it

Humans are animals🤦♀️ A huge part of the massive problems we're having is PEOPLE KEEP DENYING THAT. We're great apes🦧