The energy blindness that enables our digital creativity and entertainment — for now

A letter to the digital creatives of this moment

Dear Creative industries, I love you, but we have a problem. You talk about wanting to grow. According to a recent report by CreativeUK:

Creative industries organisations have higher growth appetite than the general population, with data from the SME Finance Monitor in 2023 showing that 72% of creative businesses were anticipating growth, versus 59% of businesses as a whole. Our survey finds that within the creative industries, Fashion Design, Film & TV and IT & Software organisations are particularly likely to seek growth, and that organisations that hold intellectual property (IP) or produce events and experiences are more likely to report having long-term growth ambitions. — CreativeUK (2025) Unleashing Creativity: Fixing the finance gap in the creative industries, p. 8.

But growth is not what we need now. It comes with a price that falls for generations after us to pay. Nevertheless, the study cited above calls for more investment into the creative industries. The imperative of investing is considered as “an inspiring call to action in turbulent economic times”, according to Creative UK’s Chief Executive. The need is framed around the hegemony of economic growth:

Anticipating growth is one thing, but actively seeking it is another. In our survey, we also ask organisations whether they have a desire to grow their business. As many as 56% of respondents state that they currently have a desire to grow, and 66% say they have a long-term plan to grow their business. (Unleashing Creativity, p. 19.)

When survey questions are framed around the verb “grow”, you get answers that relate to growth. Rather than, say, to “sustain”. In the growth hegemony, seeking to stay small and sustainable is considered lacking in ambition and in “investment readiness”.

I suggest the creative growth agenda is a) about needing to fall into line with the prevalent narrative about economy and political power and b) filled with assumptions about creative practitioners’ motivations, including that quantifiable growth by economic standards is one of them. Furthermore, c) all this is underpinned with blindness towards energy implications.

Grow or…just keep on keeping on

But is growth really the thing that creatives and artists think about when they get out of bed? I was recently watching the documentary Bird on a Wire, a collection of footage and impressions from Leonard Cohen’s troubled European tour in 1972. In the film, a journalist asks Cohen about how would he define success? The great singer and poet hesitates for a while and then answers, ”I think success…is survival.”

I mention this because I believe that is how artists and creative minds initially think about the opportunities for expressing their talent. That it is, survival both in terms of the undying need to express themselves but also as an opportunity to keep going, when one gets the acknowledgement from an audience that pays attention. The issue today is that many artists, mostly in the Global South, reach scales of success where the aspect of survival becomes secondary and self-actualisation (in maslowian terms) becomes primary, often buoyed by ballooning egos and attachments to material wealth. The stories are many, so they become aspirational stories of ‘an industry’, adding to the growth narrative.

Over three decades, I’ve had roles in companies within the creative industries and interacted with tens of creative companies through my work. Over the years, I’ve facilitated tens of workshops focused on creative problem-solving and leveraged research on creativity (e.g., Keith Sawyer’s work) to inspire the participants to engage with the type of divergent thinking that creativity rests upon.

When companies in the creative space seek growth, in my experience they seldom target absolute economic growth, but rather the opportunities to keep making creative things and to make more of them. They seek business sustainability as a way to secure outlets for their creative energy rather than outright growth. If, coincidentally, the growth becomes real, often it is the business school graduates that come in with their metrics and strategies to change the trajectory towards larger scale operations and profit.

Someone might say that the initial lack of ambition (in capitalist terms) in such creative endeavours is characteristic of a ‘cottage industry’. However, the term cottage industry is often used in pejorative fashion to describe an area of creative practice that has not reached the heights of revenue or profitability that modernity privileges. Or, technological prowess. The term also tends to have a misogynist flavour to it, referring to artisan practices typically practised by women — you know, dabbling with something cute but less than profitable.

The alternative take is to celebrate cottages and live by the edict ‘small is beautiful’. I suggest that a more modest disposition towards creativity, one that is not obsessed about its economic implications, is more to true to creativity’s mysterious origins and more aligned with its relationship to energy.

Creative energy

Whether the goal is to grow, survive, or even downscale (degrow!), the process takes energy. There’s not a consensus about how to define energy, but at the end of the day, without energy, living beings can’t do anything. When we harness energy from nature, it enables us to act and think, and when we power our technological inventions with energy, they transport, lift, illuminate, compute, and so on. When we have more than enough energy to cover basic needs, we channel that energy to exercise, play, thought, and creativity.

Energy and creativity are interconnected. In Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, Elizabeth Gilbert defines creativity as “the relationship between a human being and the mysteries of inspiration”, but creative expression is not limited to humans. Nature displays myriad ways of creative problem-solving, ranging from single-cell organisms navigating complex environments in search of food to plants reaching for sources of light in changing circumstances.

When energy is harnessed into activities that attract non-trivial, novel solutions, or energy manifests in an expressive (rather than purely functional) output, we can talk about creative energy. This, too, we typically attribute to humans and our capacity for imagination, but creative energy has also been understood in less human-centric ways. The Wisdom Library, a collection of writings from various wisdom traditions, offers a summary of creative energy:

Creative energy is a multifaceted concept across various spiritual and philosophical traditions. In Tibetan Buddhism and Vaishnavism, it represents intrinsic forces enabling renewal and the manifestation of the material world, respectively. Purana attributes it to the divine essence that facilitates creation, while Vedanta relates it to Brahma's creative power. In Shaktism, it is the feminine embodiment of energy, while India’s historical context highlights it as a source of artistic and societal dynamism. In science, it’s viewed as the divine source behind creation itself.

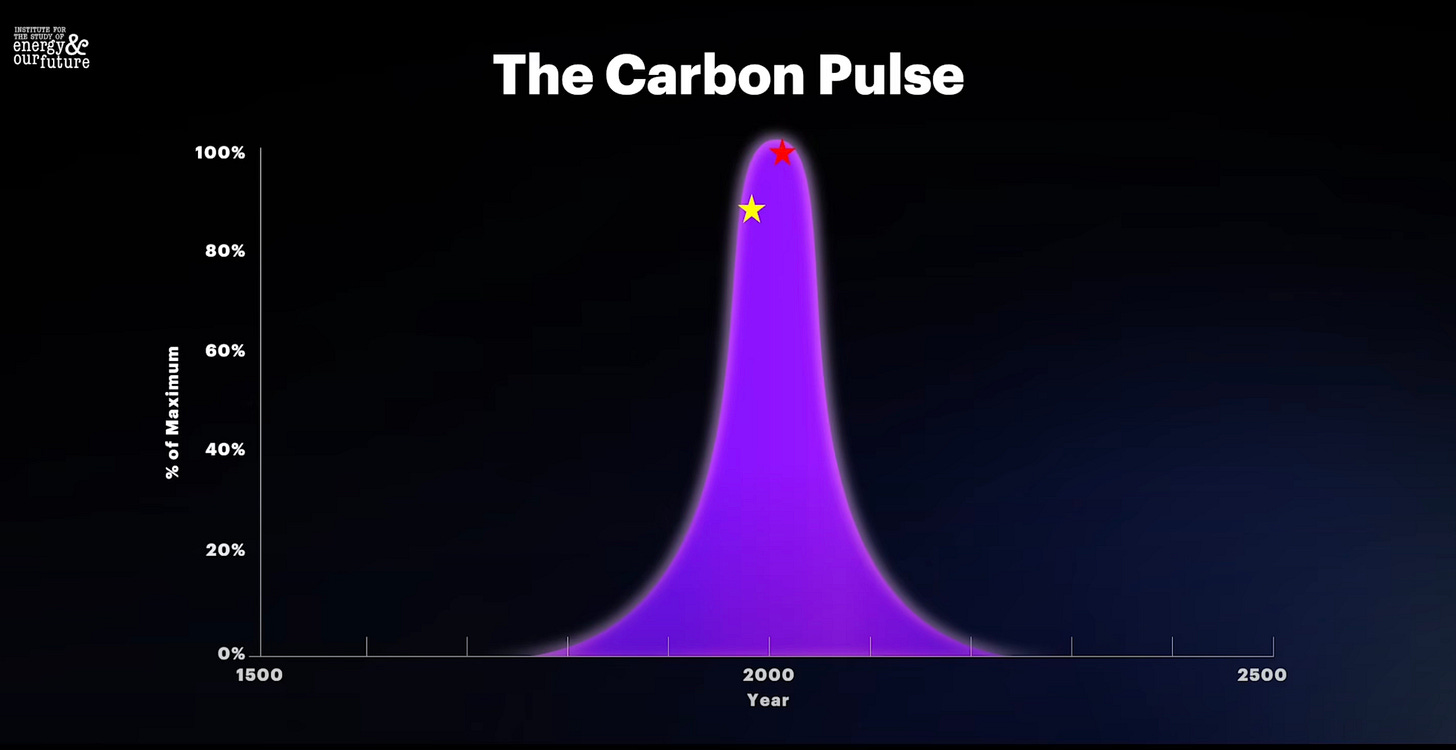

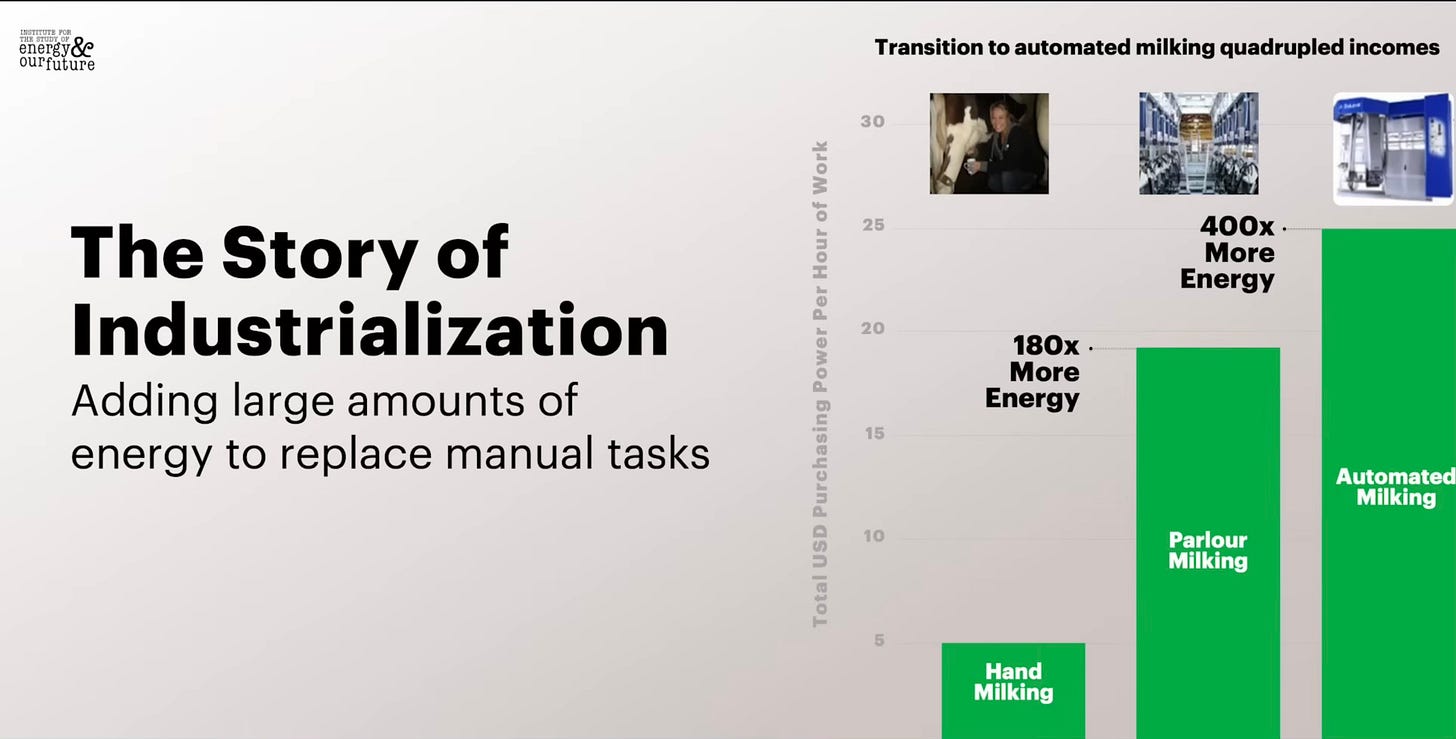

In a previous post about innovation, I touched upon the notion of energy surplus and the creative energy surplus as a byproduct of it. The idea is that through the inventions of the industrial revolution, made possible by modernity/coloniality, the Global North amassed the necessary energy reserves to build the modern lifestyle. The reserves freed up time and energy for individuals to strive for building businesses that seek scaling beyond local needs and without ties to living off the land. Creative endeavours emerged into ‘industries’ too, whether to the scale of cottages or to global heights, as with the film industry. However, from a historical perspective into energy production, the energy surplus that enabled all of this looks like a pulse instead of an endlessly climbing upward curve. And a pulse only persists for a limited time before a flatline follows.

The risk is that in seeking endless growth and abundance, our industries, including creative, are contributing to the end of the pulse; the drop off a cliff.

Energy blindness

We need and consume energy, that much is clear. But in the process of taking it for granted, we have become mostly ignorant about where it comes from and how it should be managed.

The great

’ talk “Power Shift: Shattering Illusions about the Energy Transition and Our Future” is essential viewing — I beg you to watch it. Nate builds his argument on a wealth of data and the notion of the carbon pulse, i.e. that we are living in an era where the global culture “is drawing down the stored potential energy in carbon and hydrocarbons, coal oil, natural gas, 10 million times faster than it was trickle charge by daily photosynthesis”, as he put it in William Blair’s podcast.

For Hagens, “energy is the single most important variable in our global culture” because technology and economy reside as layers on a pyramid where the invisible energy surplus is the foundation. It enables everything. Every single good or service on Earth necessitates energy for their invention, manufacturing, distribution, repair, and disposal. Energy is primal in all the systems of nature, and therefore also in all human-built systems.

The fact is that however much creative energy we sustain, us working in the creative industries are increasingly attaching ourselves to digital tools that consume energy from finite sources as if there were no limits. As John Michael Greer notes in The Wealth of Nature: Economics as if survival mattered (2011), no nation can just print more energy like they print money. And regardless of how much money you print, it does not conjure energy out of thin air. But we seem to be under such an illusion every time we open ChatGPT or a similar tool — too often just to put some garbage in to get garbage out.

Greer also points out how the centrality of money in our current economic system (at the expense of energy) is explained by the availability of cheap energy, but that is a historical anomaly. He refers to 20th century economist E.F. Schumacher’s notion of primary and secondary goods, where secondary goods (today, e.g., our digital goods and services) can only be produced to the extent that one has access to the primary goods produced by nature. We have failed to understand (myself included) that energy is primary for getting just about anything done in the current societal systems, and we behave as if it would be infinite. While oil production has increased recently, the increase has come from shale oil instead of crude oil, i.e. we are sucking the last drops from the bottom of the milkshake can. And while AI solutions might help us find the drops that have thus far been hiding from us, the energy used for such prospecting, and even to get there, will be significant. Another knock on the pulse.

In a report titled Energy and AI, even the International Energy Agency focuses overwhelmingly on the implications for consumption and demand of energy for data centres, and the resulting carbon emissions (fair enough), but assumes that the energy deficit to run the models will be covered by growth from renewable energy sources. As Nate Hagens shows in his presentation, renewables have not replaced anything thus far, i.e. there has not been any of the much talked-about energy transition — rather, renewables have covered the increase in demand, just about. Their coverage would need to rise by minimum at the rate that the fossil fuel sources diminish and huge data centres are built.

Besides generative AI, the creative industries embrace energy-hungry rendering, display, cloud, and network technologies. Tellingly, the abomination of these developments is found in Las Vegas: the Sphere, a spherical entertainment venue covered with LED screens. However, it is far from an abomination to those who have bought into the delusion of infinite energy, or are ignorant of energy considerations in general — rather, for them, the venue is an awe-inspiring culmination in the evolution of entertainment technology. The dome reportedly consumes energy equal to 21000 homes and produces emissions equivalent to 10000 cars. In addition, there is light pollution and tons of energy invested into creating the high-fidelity, data-intensive content for the spherical display. To be fair, 70% of the venue’s energy does come from solar sources, but regardless the question remains: to what end? To motivate people to travel from afar to experience fleeting moments of awe, similar to what could be attained in immersing into nature? To implement, in the name of entertainment, measures that seek energy efficiency, when the more defensible questions for coming generations would be discerning questions about energy sufficiency? To prevent that solar energy being channelled for more regenerative needs?

The image below from Nate Hagens’ talk depicts how our technology development has skewed towards the types that increase energy demands.

Hagens suggests that renewable energy technologies are the right answer but to the wrong question — instead of how to use renewables to keep the current system growing, the question should be about how to use them to guarantee a 1000-year view that seeks to sustain all species on Earth. He uses the term ‘Goldilocks tech’ for the optimal technological responses, meaning that the technology required should not be too hot in its energy-intensity, but not too cold either because then it does not support the innovations and creative endeavours towards living facing the carbon pulse and living with its implications.

I am not promoting abolishing (digital) entertainment; I am promoting discernment in how and why we produce it, and in what scale. Where do we draw the threshold of reasonable energy requirements for creative expression is part of the recalibration necessary for the coming decades. Where and how should we channel creative energy while aware of the impending collapse?

”Rewilding” creative practices

Creative expression, and enjoying its fruits, has clear ties to mental health and well-being. The therapeutical impact of art and creative practices is well-documented. But they don’t need data centres or GPUs. This is where I find — again — one of Dougald Hine’s questions about the work to be done in the ruins useful: what is there, in creative practices and technologies, that we’ve left behind that could be salvaged for the time of endings, and reframed for a renewed purpose?

Detaching oneself, or one’s creative business, from the rat-race and determinism of digital adoption in a measured way, is one path. A fellow substacker and illustrator Tom Froese recently wrote about how he has “re-wilded” his creative process. He writes about how the expansive nature of digital tools became a maze of myriad options that began to bloat the process: “I suppose the idea is to stop trying to control everything so much. To step aside and make a way for the natural good to grow and do things that couldn’t be possible with more left-brained interference.”

For me, this expresses the idea that instead of seeking creativity via tools and things (technology), one can seek creativity in relations; in how the expression finds it form in something that has been put in motion and not objectified. This kind of approach is about being in creativity, to use Erich Fromm’s dichotomy, instead of ‘having’ creativity where the creativity is evaluated solely through the end product and the creative act itself is commodified. The notion of economic growth through creativity hinges on this premise; it is a precondition for growth in modernity’s scales that creativity is packaged into products or services.

While I don’t suggest our children should only play with sticks and stones, or draw only with pen and paper, I do believe maintaining a connection to forms of ‘feral’ creative expression and play is critical, regardless of one’s age. Rewilding has the potential to awaken our perception of energy; to see the energy implications of one’s creative acts instead of being blind to them. Attention as a moral act, as Iain McGilchrist says.

The fact that energy resources are finite rather than infinite; that we are riding the top of the pulse for now, speaks for giving consideration for several principles, such as:

the more we use energy-consuming tools of today, the less we have to rebuild once the pulse is over — the energy surplus will be gone

for example, the more we use AI today in search for economic growth, the less we can use it for regeneration later

the more we spend energy into maintaining long supply chains, as a byproduct of subcontracting the manufacturing of daily supplies to the somewhere where labour is cheaper, the less we can rely on them once the shit hits the fan

the more we direct creative capacity and the energy it consumes to extractive and profit-seeking rather than regenerative ends, the less time will the future generations have to enjoy the luxuries we have had up to now

Instead, the less we seek economic growth, the more we delay the drop of the pulse; the cliff’s edge. That might buy us time to redesign creative industries into a mould that supports the spine of our civilisation, for it to bend but not break.

Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

All your points covered here, Aki, are compelling. Thank you for your truly thought-provoking articles. As a creative, I often wonder when the tech will be enough and how far it has to go before being accepted as sustainable satisfaction. Those will always seek more "power," regardless of the category and means.