What would relational technology design look like?

Relationality: the Z axis where technology and spirituality can meet

The relational axis points to the ways in which spirituality manifests and is developed through the encounter with others. - Gabriel Fernandez-Borsot, Spirituality and technology: a threefold philosophical reflection, p. 16.

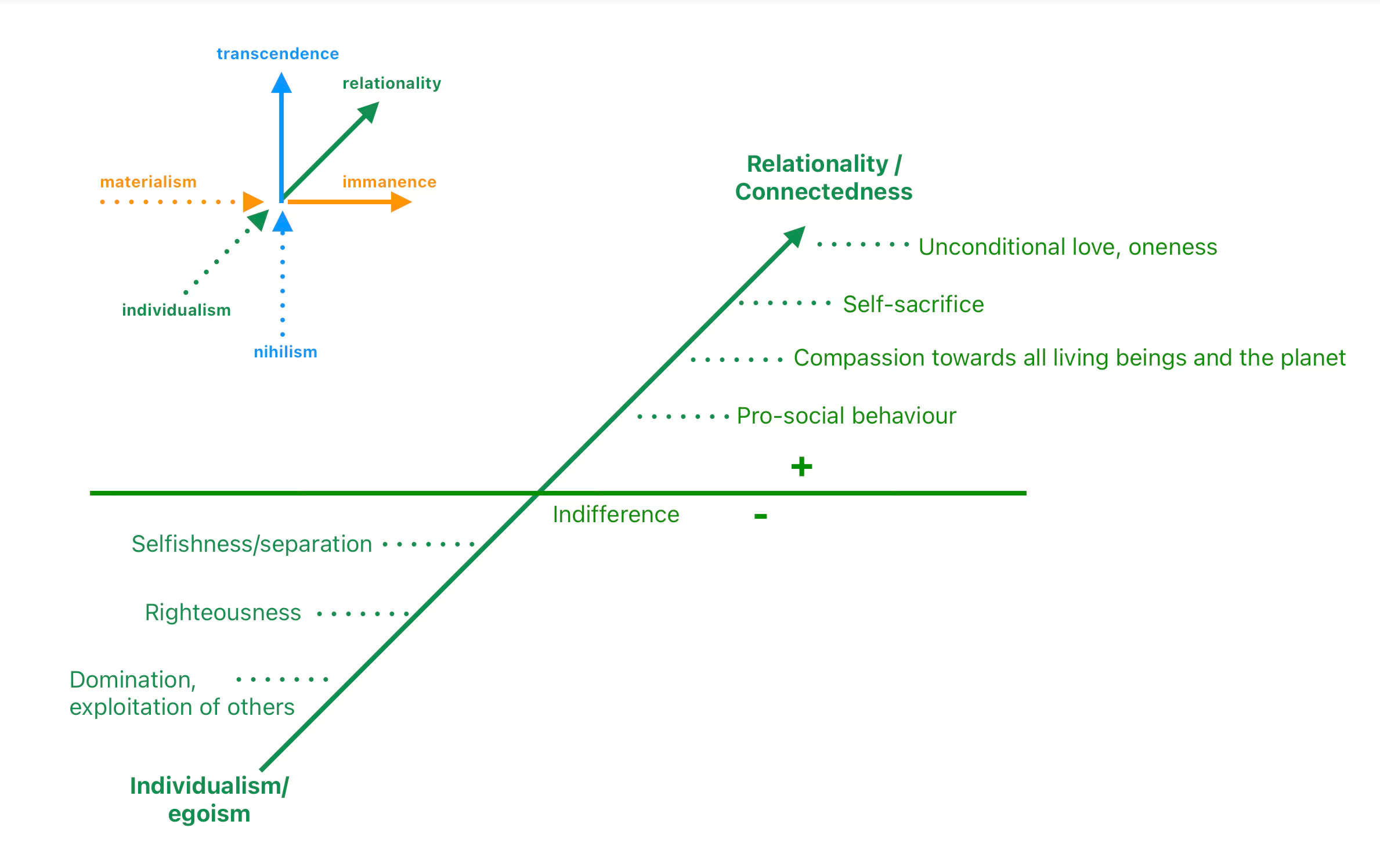

This is the final part of the series (part 1, part 2, part 3) where I explore the conceptual intersections of technology and spirituality, with the practical purpose of sketching a framework that adds the dimension of the spiritual, or the sacred, to discussions about value or ethics-based technology design and development. I’ve been using Professor Gabriel Fernandez-Borsot’s premise, i.e. that the axes of transcendence, immanence, and relationality can help us in reframing how we think about the intersections of technology and spirituality. After unpacking transcendence and immanence, we have arrived at relationality.

Relationality can be approached from multiple angles: first, it can be considered as a metaphysical principle, as for example, Iain McGilchrist does in emphasising that no things exist in isolation, but everything exists through relations — something that various wisdom traditions in both east and west have posited for centuries.

Second, questions of relationality focus on how it manifests in interactions between beings. John Vervaeke talks about the different modes of knowing, the ‘four Ps’. One of them is participatory knowing — knowing through engaging with the world. Participatory knowing is by definition relational, and when it happens in the company of others, even more so. I suggest that personal spiritual practices help in achieving participatory knowing on an individual level, and when one engages with spiritual matters as part of a community, it fosters collective participatory knowing. At its best, relationality is about loving interactions among beings.

To tie the relational axis to the immanent one (the topic of the previous post), I propose that there is a shift from the embodiment of immanence to relational embodiment; expanding the knowing that arises from within individuals to co-existing with others and nature. Relationality, then, is also about awakening to the fact that we are part of nature (which is seemingly obvious but nowadays all too often forgotten).

In the previous post, I touched upon the Heideggerian concept of forcing out things from nature with technology. Fernandez-Borsot points out how that, as the process and fascination with technology, tends to lack the relational dimension:

relational spirituality seems a much-needed complement to the technological stance. This complementarity can be seen using Carutti’s (2014) notion of bonding intelligence, defined as the ability to be enriched and transformed positively by bonds and relationships. It points to the capacity of being open to the other to a level that transforms the self. This is what is missing in the technological forcing out. - p. 18.

Relationality is also about trust, about the ability to engage meaningfully and without fear with what we exist in relation to. It is about how to direct one’s attention, with love, and unconditional love in particular as its culmination — love as paying pure attention to the existence of another, as I have heard it defined.

Relationality and technology ethics

Spirituality fosters relating to others and the world. The practical dimension of spirituality, in terms of relations, is caring about others and the environment. The idea is that humans flourish in relation to one another. This is a notion that is found in various wisdom traditions around the world, from Confucian ethics to Ubuntu. They all emphasise prosocial behaviour and how the essence of being human emerges from relationships to others instead of individualistic interests.

Technologies, communication technology in particular, mediate our relationality in various degrees:

Care and respect can materialize effectively in the promotion of technologies that distribute power, promote participation, aid those in need, and help envision a better future for all. -Fernandez-Borsot, p. 18.

Technologies enable us to connect with others, but as Fernandez-Borsot argues, technological connectedness “easily degenerates into domination and exploitation”, with surveillance capitalism as the recent culmination of such degeneration. In these cases, a different kind of power dynamic is established, a power dynamic that is not about care.

Spiritual awareness can help us tune into the predicament of others. Spirituality is about self-inquiry, to help us detach from thoughts and beliefs that are results from years of conditioning. Letting go of thoughts and ideas enables us to connect to something greater than oneself — relationally. Spirituality can help us to see the value in identifying with a larger whole and to let go of egoistic, righteous-seeking habits. In the words of Fernandez-Borsot, “spirituality provides the grounds for bonding intelligence, which in turn is the antidote to the tempting use of technology for dominance.”

As Shannon Vallor points out in the quote below, technology has extended relationality in time and space in ways that make the connections difficult to identify and negotiate:

While ethics has always been embedded in technological contexts, humans have, until very recently, been the primary authors of their moral choices, and the consequences of those choices were usually restricted to impacts on individual or local group welfare. Today, however, our aggregated moral choices in technological contexts routinely impact the well-being of people on the other side of the planet, a staggering number of other species, and whole generations not yet born. — Shannon Vallor: Technology and the Virtues, p.154.

These issues point to the complex question of technological development and ethics. The question is complex only in the sense that it requires effort and temperance from the parties involved in building technology. The effort might at times be inconvenient (“let’s just move on and break things”) but it is necessary in all research, design, and development stages. It is also crucial in all decision-making that concerns the design, purchase, and use of resources, treating the workforce, and how the technology is marketed and deployed.

Our systems feed unfair relationality

“Who are we? From the perspective of relational spirituality, we are the ones who take care of every other being, while technological development fosters a narrative focused on how, through technology, we overcome limits and explore the possibilities of the universe. The narrative of technology is not unethical; overcoming limitations is often connected to remedying suffering and protecting life. But in its autopoietic (i.e., self-maintaining) logic, it is refractory to otherness: it seeks solutions apart from dialogue, and its focus on achieving goals makes it prompt to ignore care and respect for the aspects that are not included in the goals.” — Fernandez-Borsot, p. 17-18.

Selfish and harmful behaviours are displays of our limitations as human beings. We build technology to surpass our limitations: to surpass distances, to surpass harmful viruses, to surpass forces of nature. Yet, such efforts in technology can become blind to those who are not in the immediate reach of the latest technology, thus creating inequality of needs and access. Instead of providing care and unity, the fundamental relational tenets of spirituality, technology often fosters divisions.

The technology we build mirrors who we are as a society. If we build social platforms that reward negativity, narcissism, and anger, there is something in our culture that both feeds the technology and demands it. If we build mobile phones that require materials that feed unfair practices in the global south, such as mining Cobalt in horrible working conditions, we have lost sight of what it takes to make anything even remotely complex. In so doing, we reinforce the divides. If we build and use AI systems that require unethical ‘ghost work’ in the global south, we have lost the relation, or even the notion of it, between ourselves and those who play a part in making our convenience and productivity possible.

Rather than applying scientific findings to build the tools ourselves, today we encounter technologies on a systemic level, as part of the structures of society. Therefore, any changes in how we encounter and adopt technologies need to happen on the structural level, i.e. in the types of policies and regulations we enact on the technologies we build and steward ourselves as their makers. Fernandez-Borsot writes:

The strong impact of technology, in particular digital technology, on human relations, shows how the relational domain is not shaped only by individual decisions, but also by systemic structures, with technology being an important aspect of these structures. If spiritual traditions are to effectively promote care and respect, it is not enough to foster good deeds, they have to promote structural changes. — p.19.

Unfortunately, I am finding it difficult to see how actors in our current political systems would bring about such changes, unless the machine collapses altogether. Me switching to a Fairphone (for transparency, I haven’t yet), or even hundreds of us doing the same, is not without meaning. But it won’t exactly unravel the power structures in the mobile market and the global supply chains.

Therefore, the change needs to happen in the paradigm within which we currently build technology, embraced by the makers — Fairphone and similar initiatives show the way, but we need a stronger movement, based on critical technical practices and awakenings where the scope of attention we pay to smartphones (and technologies in general) is put into question; where the business models that drive technology today are put into question. It’s planet-centric design, by minimum. Such a movement can benefit from wisdom and spiritual traditions, and I’m trying to point out potential connections with this publication.

The coordinates for relationality

As I have maintained throughout this series, the awakened design approach is — for now — untested and its coordinates are far from absolute (nor will they ever be). I like the saying, “all models are wrong, but some are useful”, hoping for the proposed model to lean towards usefulness

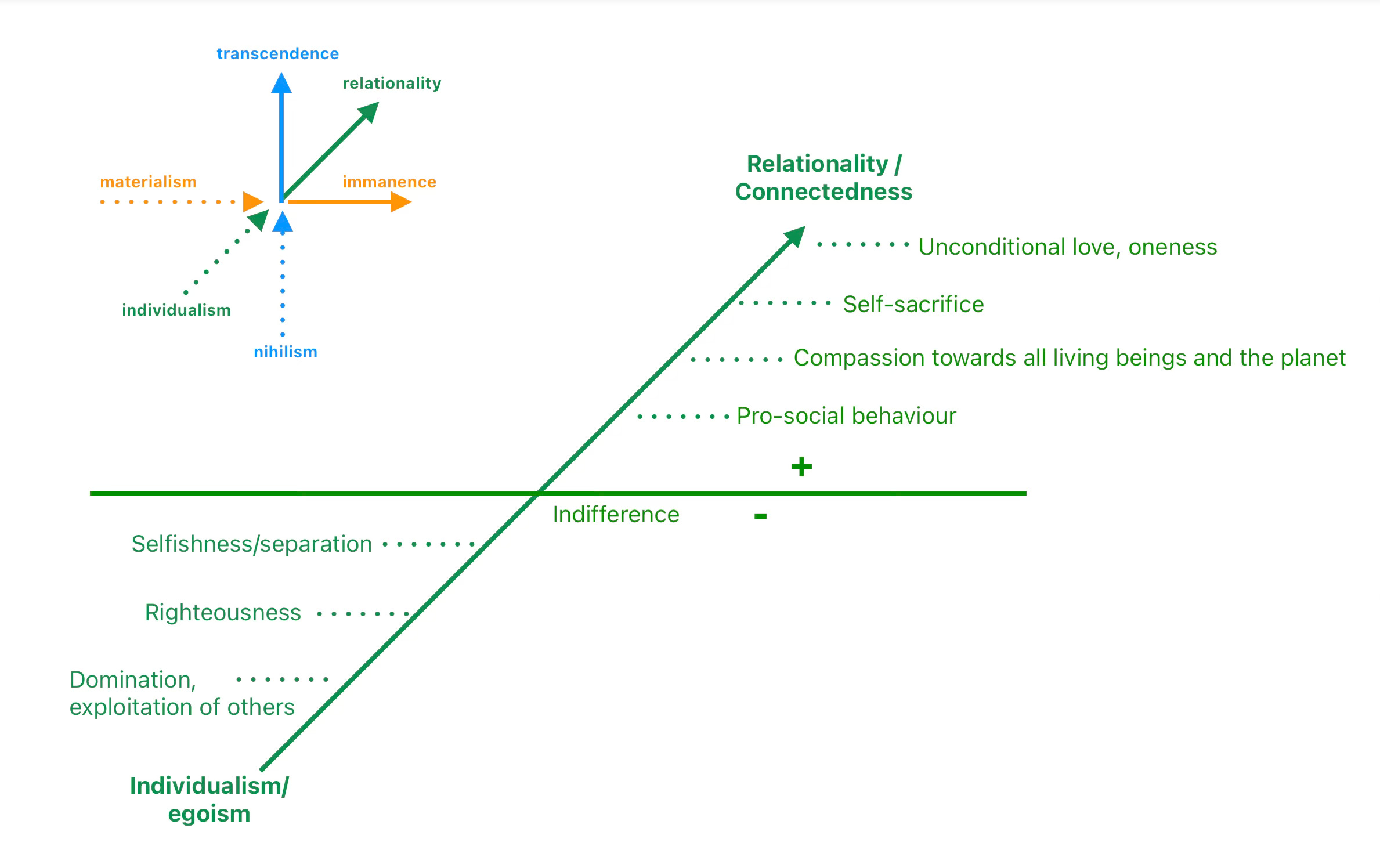

Please consider the coordinates for relationality and connectedness (and the ones on the other axes) as a sketch, a back-of-the-envelope discussion starter. They are meant to inspire thinking about how to design away from individualism and from affording egoistic motives and towards relationality. In the process, we have an opportunity to relieve suffering for ourselves and others. Adyashanti writes:

From the egoic point of view, it’s vital that we remain in conflict to some extent, and that’s why, when we look at the world around us, we see so much conflict among human beings. It’s not just because conflict is inevitable. It’s because, as long as we’re stuck in the egoic state of consciousness, we’re extraordinarily prone to be pulled into this vortex of suffering, because the ego needs the vortex to maintain its sense of separation and to survive. — Adyashanti: Falling into Grace, p. 67.

Again, this axis does not function alone — it takes part in creating a three-dimensional design space where the spiritual qualities of relationality, immanence, and transcendence reside and towards which I propose technology development should aspire (see the image below). To achieve that, to grasp the dimensionality, it is helpful to approach the individual axes and build towards the connected space around them (hence the three individual essays).

We need to design away from technologies that enable and uphold domination of others. Righteousness feeds domination, and therefore it is a coordinate we need to overcome. Righteousness feeds from a sense of separateness — seeing oneself as being correct, whether it is about a way of life, a religious leaning, a sexual orientation, a political school of thought, or a combination of all of these, something we’d perhaps call an ideology. Such leanings often do bring people together, but too often single-mindedly: the dilemma is how to channel the relational energy so that one is a member of multiple communities with differing yet not entirely conflicting values.

Letting go of righteousness and seeing the connectedness of beings are among the coordinates away from individualism, past indifference, and towards relationality. On the other side, any pro-social behaviour, any act that seeks to acknowledge the giving to others and taking from others with gratitude and respect, feeds compassion and a sense of unity. Compassion will find its ultimate expression in self-sacrifice, for example in parenthood or caretaking, exemplified also by spiritual icons, such as Christ as the embodiment of self-sacrifice. Ultimately, what lies at the end of the axis is unconditional love, not just towards those close to oneself but to towards all living beings.

How to embed relationality in technology?

How to conduct one’s technology design and development practice so that it becomes aligned with relationality? As with the other axes, this is the practical question — and I don’t have satisfying answers just yet. Aligning with relationality is not about adding a ’share with your friends’ button to a social media app, designed to fuel ‘engagement’ in its shallow and forgettable forms. We’ve been there, done that, and seen where it leads to.

Us technologists need to get better at aligning with relationality. Again, I acknowledge methodologies such as value sensitive design. They are not in contradiction with the awakened approach I argue for here, but to the (limited) extent that I have researched the topic, spiritual dimensions have not been explicitly articulated or embedded in the majority of cases where VSD has been put into practice. Certainly, having researched responsible innovation frameworks, I found no explicit signs of spiritual considerations. Transcendence, immanence, and relationality offer concepts with which we can deliberate how our practices with technology might reflect an awakened spirit.

As always, I leave you with a piece of contemplative algorithmic art.

With love and kindness,

Aki