Modernity has already restricted the parameters of what we can think, relate, imagine, and desire; and our intellect alone cannot interrupt this in time: modernity is faster than thought. This is why we cannot simply think our way out of modernity. Whatever we imagine when we are still invested in modernity will always only be a different version of modernity that secures the entitlements and enjoyments modernity affords us now. Because these entitlements and enjoyments are based on violence and unsustainability, we are back to a circular pattern of systemic harm. — Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity. Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (p. 121)

I’ll start today with another anecdote from visiting home a while ago. I had beers — yes, there were quite a few during this trip — with another dear friend, someone I studied with while at the university. I mentioned the notion of modernity, to which he responded with amusement, “wow, I sure did not expect us to talk about _modernity_ today!” The reason for his bemusement was that modernity figured frequently in our chats thirty years ago, thanks to a professor who introduced us to thinkers like Stuart Hall, Zygmunt Bauman, Raymond Williams, Donna Haraway, and many others.

However, my friend’s reaction got me thinking about the ways that modernity hides its traces if you don’t keep an eye on it. As an umbrella concept about the ethos that permeates our everyday lives, modernity had hidden itself from me for the last 25 years, and it seemed to have fallen into oblivion for my friend. Nevertheless, as the night went on, as with my other friends during similar conversations, I felt that the rationale behind mentioning modernity became more tangible. I’d like to think that a seed of awareness about the hidden moves of modernity was sowed. I am not suggesting that one needs ‘beer goggles’ to see through modernity’s facade — but every so often it helps.

Yet, the project of hospicing modernity, as Vanessa Machado de Oliveira frequently makes clear, is not to make anyone feel good — certainly not those of us in ‘the north of the north’ who have enjoyed modernity’s comforts without thinking about complicities to harm. So there, even if the mention of beers lifted your spirits a bit, I have now ruined any feel good moments for anyone reading. Stay with me, please.

The strategies for adopting the hospicing mindset

In the first part of this series, I reflected on my takeaways from the first part of Hospicing Modernity. Today, I will reflect on the chapters that follow, where the author talks about the singular story forward that modernity monopolises and the thinking that prevents us from imagining alternative horizons of possibility. Towards the end of the first part of the book, the author describes seven tools or strategies with which to clear one’s mind of the affective and dispositional clutter that modernity has produced. The clutter is stuck hard, as it is a result of conditioning to modernity’s project and making us complicit in the harm.

Machado de Oliveira returns to one of the strategies, “The bus in us”, several times across the book. “The bus methodology invites us to see a whole bus of people within us. At its most basic level, this bus has a driver and many passengers who embody what has marked one’s lifetime, including childhood events, unprocessed traumas, significant others, etc.” (p. 48). In the exercises that follow at the end of most each sections, the author puts forward a specific question about how the passengers feel or interact, or the roles they inhabit.

To me, the approach echoed internal family systems (IFS), i.e. an integrative psychotherapy method where (in my understanding) one acknowledges the multiple and often contradictory roles and voices one embodies, instead of experiencing oneself as a coherent whole, and how this process has potential to unlock past traumas and behaviours.

The bus strategy invites us to accept the dialogue between the passengers and the conflicts that might arise from it. From there, it follows that “if we cannot hold space for the complexity within us, there is no chance for us to hold space for the complexities around us.” The idea is to check on the ‘temperature’ of the bus while proceeding through the book, to see how the various situations and roles in one’s life relate to the problems with modernity/coloniality.

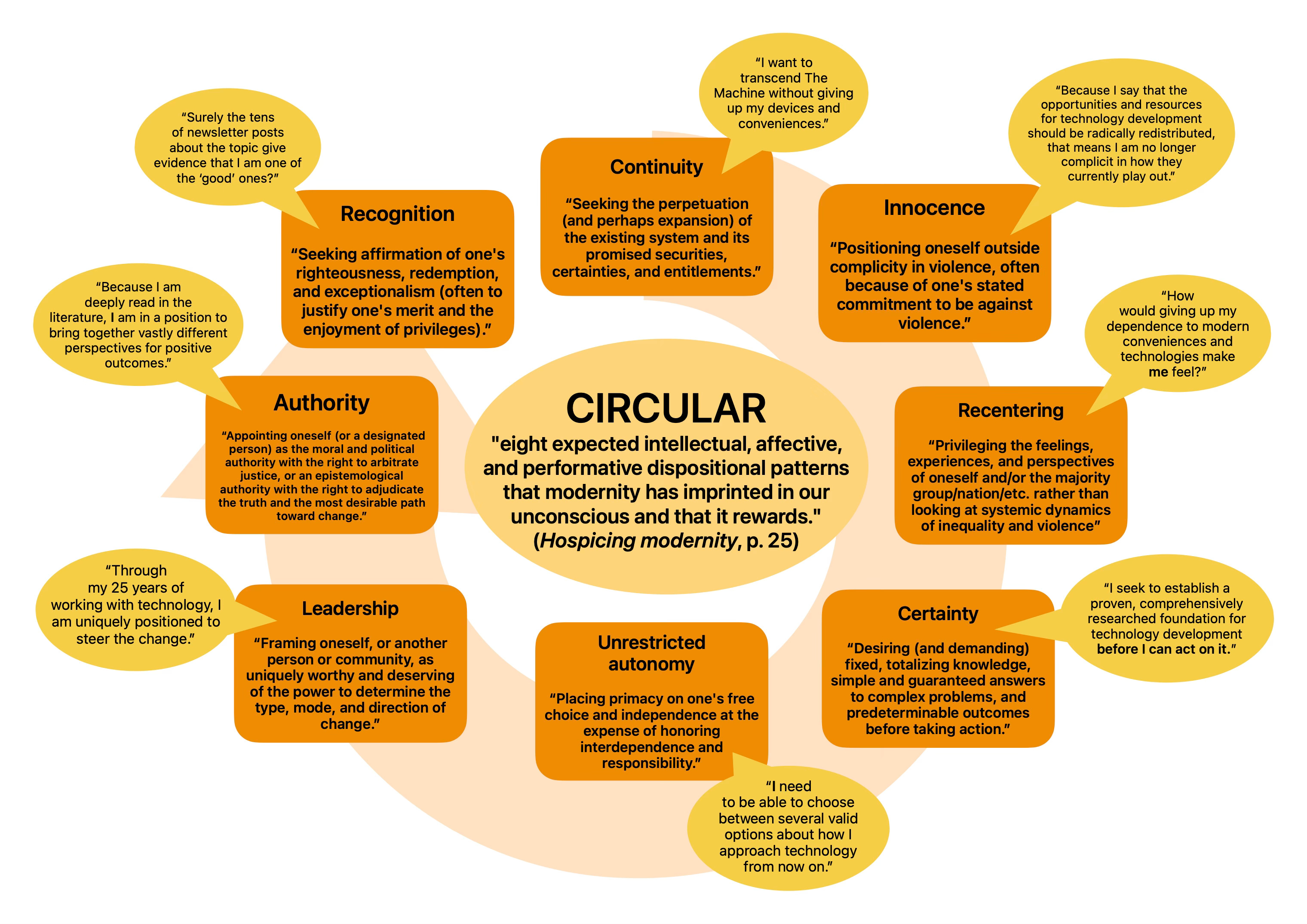

The CIRCULAR framework in the first part of the book (pages 27-8) consists of eight patterns (the initials of which make up the acronym) and offers another set of strategies for the same purpose. The reader is instructed to carry the eight patterns with them throughout reading the book. In explaining the patterns, Machado de Oliveira gives examples of how the patterns might manifest in one’s reactions, such as in the case of the pattern on innocence: “because I say that I am against violent systems, that means I am no longer complicit in them".

In the illustration below, I have reflected on how these patterns might manifest themselves to someone like me who is wrestling with their relationship to technology, whether in professional or personal contexts or both. I found that formulating such expressions, even if they are relatively off-the-cuff in their current form, helps oneself internalise what practising hospicing modernity would be. Articulating the thoughts can help in revealing egoistic and self-deceptive motivations behind one’s actions, as I’ve attempted below.

How do you react to the patterns in your context?

This mode of self-reflexivity links to the four denials outlined in the introductory part of the book:

denial of the systemic, historical and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm,

denial of the limits of the planet,

denial of our entanglement with nature while believing in human exceptionalism,

and finally, denial of the magnitude and complexity of the predicaments modernity has brought about.

Facing the denials is critical for practicing anything close to what the book invites us into. For me, the takeaways have to do with what I will do with this publication, but also considerations for short to mid-term changes beyond it, such as my research interests, and considerations for changes farther on the horizon (for example, my daytime job).

The orientations to reform

Regarding the research aspect, a few posts ago, I published a version of my working proposal for a doctorate study. Reading Hospicing Modernity, I was able to reframe my objectives with that project and articulate them more clearly. Machado de Oliveira defines three orientations concerning attempts to change the current system: soft-reform, radical-reform, and beyond-reform orientations.

Soft-reform orientation focuses on changing policies and practices within the institutions that shape the world today. Soft-reform tries to expand access to decision-making and resources, but ultimately absorbs any diverse perspectives into the existing system. In my interpretation, much of the ‘tech for good’ and equality, diversity, and inclusion initiatives around technology fall into this orientation. They strive to improve, for example, the inclusion of women into technology disciplines and career roles, but largely subscribing to modernity’s ethos. Unrepresented groups are brought in, but ultimately within the conditions of modernity, to help it sustain itself despite inconvenient interventions that try to question its premises and traditions. Ultimately, does gender equality in technology matter, if everyone is singing from modernity’s hymn sheet? Do we believe that gender and/or race alone can change the direction if the prevailing belief is one of techno-solutionism?

Other examples include areas of sustainability research, where models such as doughnut economics position themselves within the capitalist system and can therefore be interpreted as representing the soft-reform orientation. The degrowth movement, on the other hand, goes one step further, perhaps bordering on the next type of orientation, the one of radical reform.

Radical-reform orientation questions the foundations of existing systems and proposes to radically restructure them in the name of social justice. The author points out that radical reform tends to focus on singular dimensions (e.g., racism or ableism) but fails to deal with the inter-connectedness of the dimensions, i.e. intersectionality. Yet, this orientation differs from the soft one in trying to evade being absorbed into prevailing institutions, and it works towards redistributing resources and empowering marginalised subjects in their terms.

In the technology sphere, the Appropriate Technology Movement in the 1970s and 80s, is an example of an initiative that strived to enable access to technologies without some of the requirements that modernity has normalised: a high Western style education, large industrial production schemes, and commercial innovation. The movement favoured the use of local resources, among other things, but as retrospective analysis has shown, such movements can be equally biased by modernity’s values (see e.g. Malcolm Hallick, The appropriate technology movement and its literature: A retrospective). More recently, the Social Technology Network in Brazil (early 2000s) was an attempt to support a grassroots movement to build pathways of social inclusion and sustainable development, but it crumbled under different types of tensions (see Mariano Fressoli and Rafael Dias, The Social Technology Network: A hybrid experiment in grassroots innovation).

Beyond-reform orientation sees the radical approach inadequate to “shift the underlying violent and unsustainable infrastructures of the modern/colonial system” (p. 90). Beyond-reform identifies the injustices of modernity/coloniality not as byproducts but as conditions of existence, and consequently acknowledges that the current system cannot be reformed. It is about palliative care rather than providing life support (like the soft orientation does). This produces three theories of change for practical purposes: walk out of the system, hack it, or hospice it.

Machado de Oliveira recognises that not all initiatives towards changing the system can strive beyond reform. To make up for that, those working from the soft and radical positions need to be aware of the bigger picture (that she paints) and work with selfless integrity to reduce harm. The tactics within beyond-reform are not easy to pull off with integrity either — first, not everyone is in a position to make the conscious choice of walking out, and second, hacking might turn into an egoistic project with blurred boundaries between playing the system versus being played by it. The third option, hospicing, is beyond hard, given the corner many of us have painted ourselves into.

Nevertheless, using this prism of different orientations, my PhD project about studying alternative ways of knowing for the purposes of technology development, and drawing from wisdom and spiritual traditions, gets positioned somewhere between the radical and beyond-reform orientations. Yet, if I would actually be able to carry out the study, it would need to take place within the system and its mechanisms of academic acknowledgement, etc. Therefore, I am conducting aspects of the project here, yet without certain structures and benefits, such as peer reviews, and within a publishing environment that operates with a late capitalist platform logic. Then again, something less academic but more actionable and practical is resulting, as we speak, from dialogues in the context of Substack — and I am hoping to extend these activities beyond the platform, into more dialogic and communal interactions.

Yet, the need to find immediate practical applications is a left-hemisphere manoeuvre. I take hospicing modernity to be more about a gradual rise of awareness and approaching the issues with integrity, so that one would find ways to shift one’s attention away from the colonial dispositions and desires. This is not easy, but investing oneself into it builds the capability to see otherwise; to imagine otherwise. There will be lapses and dead ends, as the author warns:

Identifying one's harmful desires, which can happen through exercises of deep self-reflection or through witnessing the harm one is causing firsthand, is only the first step on the road. Interrupting our (unconscious) enjoyment of these harmful desires is another journey altogether, and it is fraught with relapses, sidesteps, and dead ends. It requires long, sustained practice. (P. 122.)

I’ll drink to that. Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

Please help me improve Unexamined Technology by filling out a quick reader survey!

I had already been working with IFS for a good while before I read the book. The bus exercise was continuing that work. I believe Vanessa directly referenced IFS in the book.