“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born:

now is the time of monsters.”― Antonio Gramsci

Gramsci wrote about monsters in the 1930s, imprisoned by Mussolini. During the past weeks, I have seriously pondered the possibility that the world has gone insane. I see monsters. How do you break this to a 12-year-old child who still holds your hand while you watch television?

Obviously, you don’t. You shelter them. Perhaps you cite, after just finishing reading Lord of the Rings, Tolkien and Galadriel and tell them that “even the smallest person can change the course of the future”.

But equally, you want to prepare them to face a world where they, and certainly, their children, are likely to have less convenience — the convenience that has become part of the repertoire of means with which to shelter them. How does one negotiate that; how does one take responsibility for taking action, fumbling for a moral compass that the leaders of the world seem to have chucked in the bin?

Someone on Substack notes recently quoted Hannah Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism and how in such movements, businessmen (men, obviously) become the arbiters of politics, and politicians have no relevance unless they learn to speak to businessmen. What is going on with the new US government represents that in an extreme form, but we are not that far from similar developments in many places here in Europe.

The compass for hospicing

Orc: ”The trees are strong, my lord. Their roots go deep.”

Saruman: ”Rip them all down.”

I would rather not put everything against Trump’s recent inauguration. It feels like a too easy of a target because the roots are so much deeper, but arguably many of the issues find their absurd culmination in that moment and the resulting executive orders. Their concreteness in tearing down the virtues of the true, the good, and the beautiful is something to truly lose sleep over. While some structures being torn down can be argued to represent the bloated spoils of modernity, they are being replaced with even more rotten incentives. There is no moral compass apart from an amoral compass.

Vanessa Machado De Oliveira talks about the ethico-political compass for hospicing modernity, where difficult conversations are to be had about 1) disinvesting from harm, 2) interrupting modern addictions, and 3) transitioning out of violence. It is difficult to see how the current mainstream political landscape can hold space for such conversations. Both politics, entrepreneurship, and knowledge production are largely driven by what Machado de Oliveira calls modernity’s imprints in neurophysiology. She refers to the dopamine hits that feed individualistic incentives and immature desires to make a difference in the world, be it via politics, business, or research. The notion of unrestricted autonomy that most of us have cherished has taken us there. It’s not sustainable, though.

As an alternative, Machado De Oliveira suggests we need to learn to live without many of the fruits of modernity, and it is only our collective imagination, curtailed by modernity’s conditioning, that has failed us so far. She writes about getting to zero, i.e. not falling to the trap of coming from the position of ‘plus one’ and ‘including’ the ‘minus ones’ in the conversation. Rather, the parties should strive to meet in the middle, in the ground zero — the ruins, if you will — of a new civilisation. Nurturing such communities and their practices at ground zero would be key.

Communities of practice

During the past year of writing Unexamined Technology, I have established connections — relatively loose, but nevertheless — to communities that contemplate life in the time of endings. Just the other day, I had the pleasure of joining such a community in the making, back home in Finland (even if online). This was as if by design; as an immigrant I had wondered how and if themes such as the metacrisis, hospicing modernity, and critical technical practice, have taken root in a country whose citizens rank as the happiest in the world and which tends to be regarded as the poster-child of modernity — when modernity is taken as an emblem of progress, equality, and so on, that is. Nevertheless, I am glad that seeds for a community over there have been sown, and I hope to participate in nurturing them.

How might such small beginnings become contagious, while breaking free from the ‘scaling’ obsession of modernity? Machado De Oliveira writes about approaches to that, but there are other voices out there that have influenced her thinking. As an example, The Berkana Institute works towards new community-led paradigm changes, founded by Margaret Wheatley whose sobering book Restoring Sanity I have cited in the past. For Berkana, she has co-written a booklet about transformational change that emerges through local networks:

Despite current ads and slogans, the world doesn’t change one person at a time. It changes as networks of relationships form among people who discover they share a common cause and vision of what’s possible. — Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze, Using Emergence to Take Social Innovation to Scale

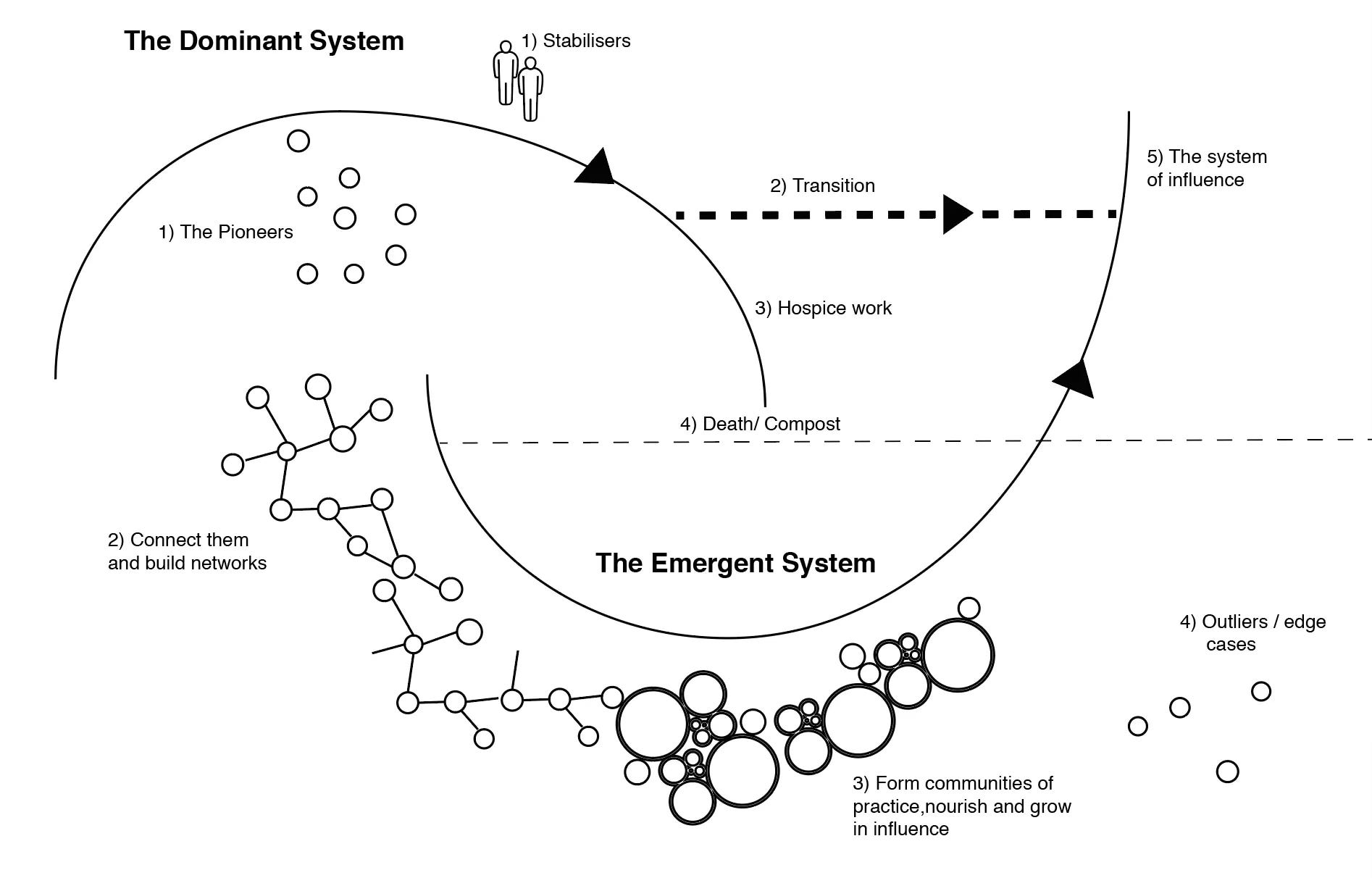

The authors write about how making a network visible as a map fascinates people, and it provides evidence of the network, but too often the dynamics of the network — the conditions it has emerged from, the ties that bind it, the leadership within, the network’s lifecycle, and resilience — are missing in such mappings. Bob Stilger has elaborated on the model and visualised it as two intersecting loops (of which more later). Wheatley and Frieze’s observations echo the ontological need to privilege the relations instead of what they relate to and bring into being, the relata. The network is only as strong as its connections, and the connections ultimately characterise what the network is for.

The gist of Berkana’s network approach is in the four stages: naming the pioneers, connecting them, nourishing their collaborative practices, and illuminating their work to others. The perspective here is articulated from Berkana’s role as a facilitator for the stages to emerge into being. It is important that the work be selfless and humble — for example, naming cannot be there to stroke someone’s ego but to enable the connections and the resulting community. In the terms of Hospicing Modernity, any such community can benefit from identifying its stance between soft, beyond, or radical reform.

Cassie Robinson has helpfully taken Bob Stilger’s visuals and iterated them into a holistic overview, as seen below:

Stilger elaborates on the function of the model:

This simple model really isn’t a theory of change, as some people sometimes refer to it. It’s a map for thinking about what is important to each of us now and where our work lands in a larger system. … The Two Loops has proved to be an effective way to help people think about what’s going on and where they stand. - Bob Stilger, When we cannot see the future where do we begin

For me, the model gives hope and strength, and literally a shape to pursue in how to collaborate on a small scale, both in person and online. Therefore, I suggest it can also be taken as a recipe for individuals when they seek like-minded others, as I do with this publication and the communities I wish to participate with in naming, connecting, nourishing, and illuminating. We can all do that, with the broader aims at heart.

Emma Proud has written an insightful piece about how to take the model into practice. She points out how the model acknowledges the importance of providing care to the dominant systems during the transitions so that even during decline things still function. Despite the monsters that are hiding in the map. And this is where we are failing at the moment. We are also failing in providing ”hospice to those who find change painful”, as Proud writes. Hospice is difficult to give, but also to take.

Naming the Gs

I haven’t written explicitly about technology today, but it will play various roles in systemic transitions, also some of it becoming compost. Hence, the degree and type of attention we give technologies — as moral acts, as Iain McGilchrist beautifully says — is of crucial importance: how might we learn to discern the life-affirming technologies to take with us to the new system?

Giving attention and discernment consumes time, the resource we certainly will not gain more of. I began the essay by quoting Gramsci and Galadriel. It’s only fitting that I will end with another major OG, with the thought that the time to put the monsters into bed is now, yet time is running out:

“All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us”

— Gandalf

Thank you for reading.

Dear reader, I have recently activated paid subscriptions. All posts will remain free. I will provide additional benefits for the paid tier, starting with spoken audio versions of older posts. In addition, if/when a reasonable number of you opt for the paid tier, I will begin a quarterly webinar series on the newsletter topics, exclusive to paying members. I realise supporting another author on the platform might be a big ask (myself I pay for three and that’s it) — therefore I have brought the rate down to £4 per month, i.e. two pounds per essay. A yearly subscription is even cheaper. Thank you for considering, and in any case, liking and sharing the posts is another valuable way of supporting my work! Buying me a one-off coffee is another :)

With love and kindness,

Aki

keep writing!