Note: I will return to my reading of Hospicing Modernity (part 1), part 2) with some final reflections in a future post. I felt it’s time to shift gears, and I’d also like to think that today’s post shows traces of how the book has influenced my perspective.

I recently shipped my remaining belongings, after 10 years (I know), from a storage in Finland to another storage in the UK (I know…). The clutter, 95% of which I have not missed, evoked feelings of shame but also made me reflect. Among the clutter there are pieces of technology that had some use back in the day but now they make me feel indifferent at best and anxious at worst. Hence, the topic of today’s post: is there a time and place for mourning about a technology?

This essay is not a self-help piece about fasting from your smartphone. It is about the broader systemic issues with technologies and their multi-tiered impacts: how might we identify the impacts technologies have had that are not conducive to planetary flourishing? How, then might we detach from a technology by detaching first from its systemic impacts and the ways they have conditioned our behaviour? What would it mean, as a society or a community, to abandon a technology?

Revisiting the field kit

Today is also a continuation on the work on the ‘field kit for work in the ruins’ (pictured below) that I’ve introduced as a tool for uncovering systemic contexts of technologies; contexts that often are not obvious and have been obfuscated through intertwined processes of needs, adoption, marketing, and politics.

“Letting the light in” using the kit, i.e. directing deliberative attention on everyday technologies and asking them discerning questions, functions as a practical tool in such inquiries. The post about microwave ovens was an experiment of what the method might be able to produce:

Microwave ovens were never as good as we told ourselves they were

A couple of months ago, I shared the first attempt at combining two approaches to asking questions about phenomena in the world — the design and innovation agency Smithery’s Where The Light Gets In and Dougald Hine’s At Work in the Ruins (now available in paperback!). The purpose was to find a method with which to ask hard questions about the technologi…

The kit initially posed the four questions, inspired by

’s At Work in the Ruins, and I’ve designed it to help deliberate the answers about the object under scrutiny. While Hine’s original questions are not technology-focused, that has been my interest in taking the questions into practice via the kit. ’ concise question ”what hidden world — with its values, obligations, assumptions, prejudices, etc. — does a technology bring to bear on the life of the user”, has also inspired me in pursuing the approach as a tool.In trialling the kit, I have tried to steer away from technologies and phenomena where the choice between the four questions seems quite obvious. Take something like vapes or gambling — my intuition is that it’s safe to say they were never any good for anyone. Although even with vapes, the present outcome was not obvious: electronic cigarettes were first introduced as a healthier substitute to smoking or as an aid to help with quitting smoking. Yet, now we are faced with the obscene environmental cost of cheap, disposable vapes. Adapting the technology for the current consumer context where offering various options (the innumerable flavours, etc) without much additional expense appears to have been too alluring to resist for the vape producers who seek quick wins within the economic system. The e-cigarette, as a technology ‘itself’, was swept away by the blindness to speed and consequence that characterises the capitalist system and the incentives it imposes on us.

As with the vape example, one realises quickly in practice that the answers are not straightforward: the kit evokes observations about the second and third-tier societal, political, cultural, and environmental impacts the technologies have had. Often, individual technologists or even teams of them do not have the mindset nor time to consider such implications. They work in corporate contexts where the driving force is what Wendell Berry has termed as ‘arrogant ignorance’:

We identify arrogant ignorance by its willingness to work on too big a scale, and thus to put too much at risk. It fails to foresee bad consequences not only because some of the consequences of all acts are inherently unforeseeable, but also because the arrogantly ignorant often are blinded by money invested; they cannot afford to foresee bad consequences. —Wendell Berry (2004), The Way of Ignorance.

Therefore, the kit is raising the hard questions by design — provided that the viewer is interested in engaging with such complexities. For us technologists, I suggest that the insights generated can illuminate design constraints and opportunities when we are considering the makings of future technologies and their applications. The questions are more important than absolute answers. Nevertheless, for the technologically minded observer, the questions might lead to insights that are challenging to face, or even difficult to admit because they implicate oneself in harm and the denial of it.

Indeed, when attempting to identify specific technologies for scrutiny, it quickly becomes evident that matching them with one of the four questions shifts the focus to the contexts rather than the technology itself — or, that there really is no such thing as technology in itself. Any technology gains its meaning through the relations it is launched into and finds its uses in. With a critical hat on, it is tempting to see the technologies in themselves neatly fall into a category (e.g. something to be mourned), yet almost without exception (the vapes, etc) it is the context, method, or volume of use that becomes the discerning factor. For example, combustion engines enable transporting people for medical care rapidly, or distribute food and medicine to those in need (‘something to take with us’). However, the volume for which they are being used in cars, in particular, for less important, often blatantly individual and habitual purposes — such as convenience — and the resulting impacts, tell a different story of the enabling technology (‘never as good as we thought it was’). And that story would not exist without the systemic relations of one technology to a host of others: cars, in their current scale of adoption, can only exist on the web of urban cities, their infrastructure, and the infrastructure linking them to other cities.

Then, a new technology comes along that addresses certain issues: electric vehicles address the emissions issue, but they don’t address a whole host of others, such as congestion which is a result of more complex, contextual developments in transport infrastructure and policies over decades. Furthermore, when you have vehicles that glide around making less noise, what does that entail for pedestrian and cyclist safety?

The Futures Wheel

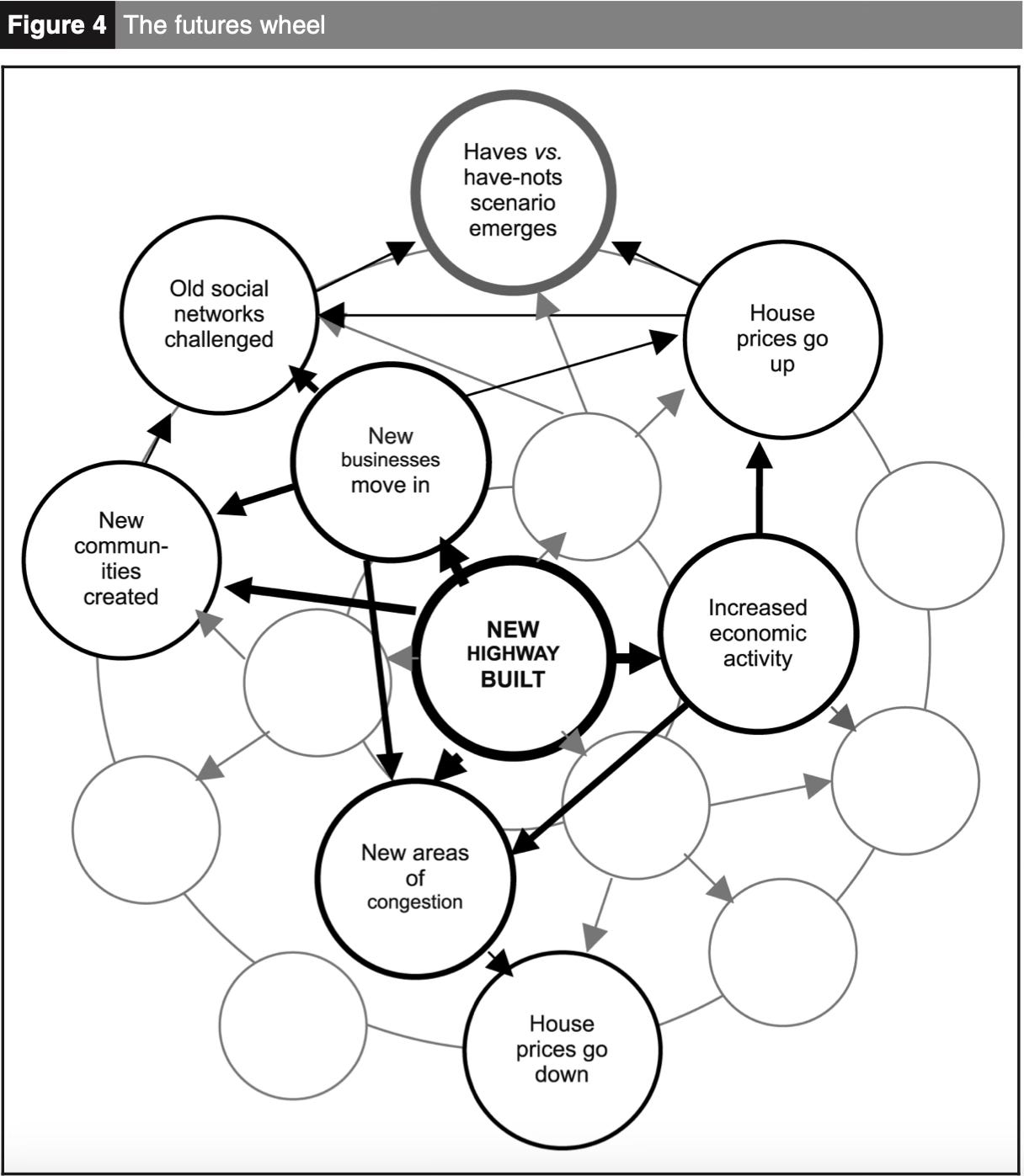

In summary, the more interesting cases to contemplate with the kit are those where the answers are not obvious and absolute. This suggests that a technology may simultaneously have inherent value and be dragged down with secondary or tertiary consequences or contexts where the technology has become exploited with thoughtless or outright bad motives. Here, the field kit approach can be combined with the Futures Wheel method, for example.

The futures wheel seeks to develop the consequences of today’s issue on the longer-term future. We can ask how a particular new technology might influence us 20 years from now. The futures wheel does not stop at first order impacts, but rolls along to second order impacts, and beyond. It intends to explore and deduce unintended consequences. — Sohail Inayatullah (2007) Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming, (p.9)

In the article, Professor Inayatullah describes six foundational concepts, six questions, and six pillars as a combined approach to studying the future. He illustrates how the futures wheel can map implications of a new highway, for instance: the highway may increase economic activity and consequently create more jobs but also, as secondary impacts, congestion, and health problems. Furthermore, while new communities may emerge when the highway connects people, there are likely impacts on house prices that will again have further impacts, such as shifts in the locus of social networks, and so on.

While Inayatullah harnesses the wheel approach to anticipate future developments, I suggest it can also be used to map historical developments. ‘Backcasting’, another futures approach, enables mapping the multidimensional consequences starting from today and proceeding backwards in time to the origin.

Yet, seeing technological developments as linear trajectories poses a risk of falling into modernity’s traps, to a left hemisphere view that the systems enveloping the technologies function like a machine with predictable outcomes. All these complexities can be considered the inner workings of modernity trying to sustain itself. To unpack these machinations, one has to focus on the relations, the ‘inbetweenness’, as much as what they relate to.

No technology can be mourned alone

Despite the potential usefulness of the above approaches, we have a problem. I cannot come up with a current technology that falls into the ”something good to be mourned” category, i.e. something that was once good but has now lived its course, and we should let it go in a dignified way.

If we look into the history of technology, it’s easy enough to identify past iterations of technological solutions that have since been replaced by an improved version, or an invention that puts the good that the old one has generated into oblivion. Progress like this has typically manifested through sheer volume or degree of improvement. This is the case with many medical technologies, for example. It is difficult to see past such iterations, and therefore I suggest the focus needs to shift into the systemic contexts. Mourning a technology becomes a side effect of mourning something in the contexts, a part of the system, that we need to let go of. For example, if we would let go of a consumerist and hedonistic ways of living, and begin to revalue durability, locality, and durability instead of being subjected to planned obsolescence, the need for disposable vapes, for example, would disappear (maybe).

Perhaps we can also mourn a technology in relation to a particular context where it once added some value to human well-being or getting by, but in the bigger picture, or through historical developments, it does not deserve that kind of status any more. Some might argue that my previous judgment of microwave ovens falls into this bucket — there was a time when microwave ovens democratised cooking, but those virtues have been overtaken by the emergence of ultra-processed foods, etc. Speed and convenience have again conquered the communal and empowering aspects.

So, should the anticipation of abandoning a technology because we cannot afford it any more, or the actual process of letting go of it begin from the tertiary and secondary effects it has had? I would suggest yes.

For care or for speed?

The systemic strengths of an approach like the Futures Wheel can also be considered their shortcoming. They abstract the phenomena from the everyday, experiential ways that we encounter them, often ignoring the lived and embodied aspects. In Becoming Animal, David Abram writes about how travelling on highways does away with the multi-sensory richness that a slower means of travel induces:

Such alterations in the unseen spirit of the land are mostly hidden to those who make the journey by car, since then all the senses other than sight are held apart from the sensuous earth, isolated within a capsule hurtling along the highway too fast for even the eyes to register most changes in the disposition of the visible. … Certainly there are roads more conducive to sensory alertness than the highway, whose rectilinear, manicured margins induce a kind of stupor in the speeding driver, a steady trance of abstraction — an onrushing flood of memories and future concerns with few ties to the sensuous present. — David Abram, Becoming Animal, p. 137

It is also worth quoting Wendell Berry here at length, when he writes about the obsession with speed and quantity over care and quality that, in the context of his writing, agricultural technologies began to embody during the 20th century:

It appears that we abandoned ourselves unquestioningly to a course of technological evolution, which would value the development of machines far above the development of people. And so it becomes clear that, by itself, my rule-of-thumb definition of a good tool (one that permits a worker to work both better and faster) does not go far enough. Even such a tool can cause bad results if its use is not directed by a benign and healthy social purpose. The coming of a tool, then, is not just a cultural event; it is also an historical crossroad — a point at which people must choose between two possibilities: to become more intensive or more extensive; to use the tool for quality or for quantity, for care or for speed. In speaking of this as a choice, I am obviously assuming that the evolution of technology is not unquestionable or uncontrollable; that 'progress' and the labor market' do not represent anything so unyielding as natural law, but are aspects of an economy: and that any economy is in some sense a 'managed' economy, managed by an intention to distribute the benefits of work, land, and materials in a certain way. — Wendell Berry, Horse-Drawn Tools and the Doctrine of Labor Saving (1978)

In similar fashion, vapes and even highways replicate this drive, and we are certainly, to borrow Berry’s phrasing, at a historical crossroad regarding AI — “to become more intensive or more extensive”, and whether to use AI tools for quantity rather than quality. Similar deliberations apply regarding the areas we should adopt AI in — they should be chosen with care rather than with the speed that both governments and individuals are scrambling towards them. Communal and empowering applications of AI, in education for instance, instead of speed and convenience.

The values in and through nature

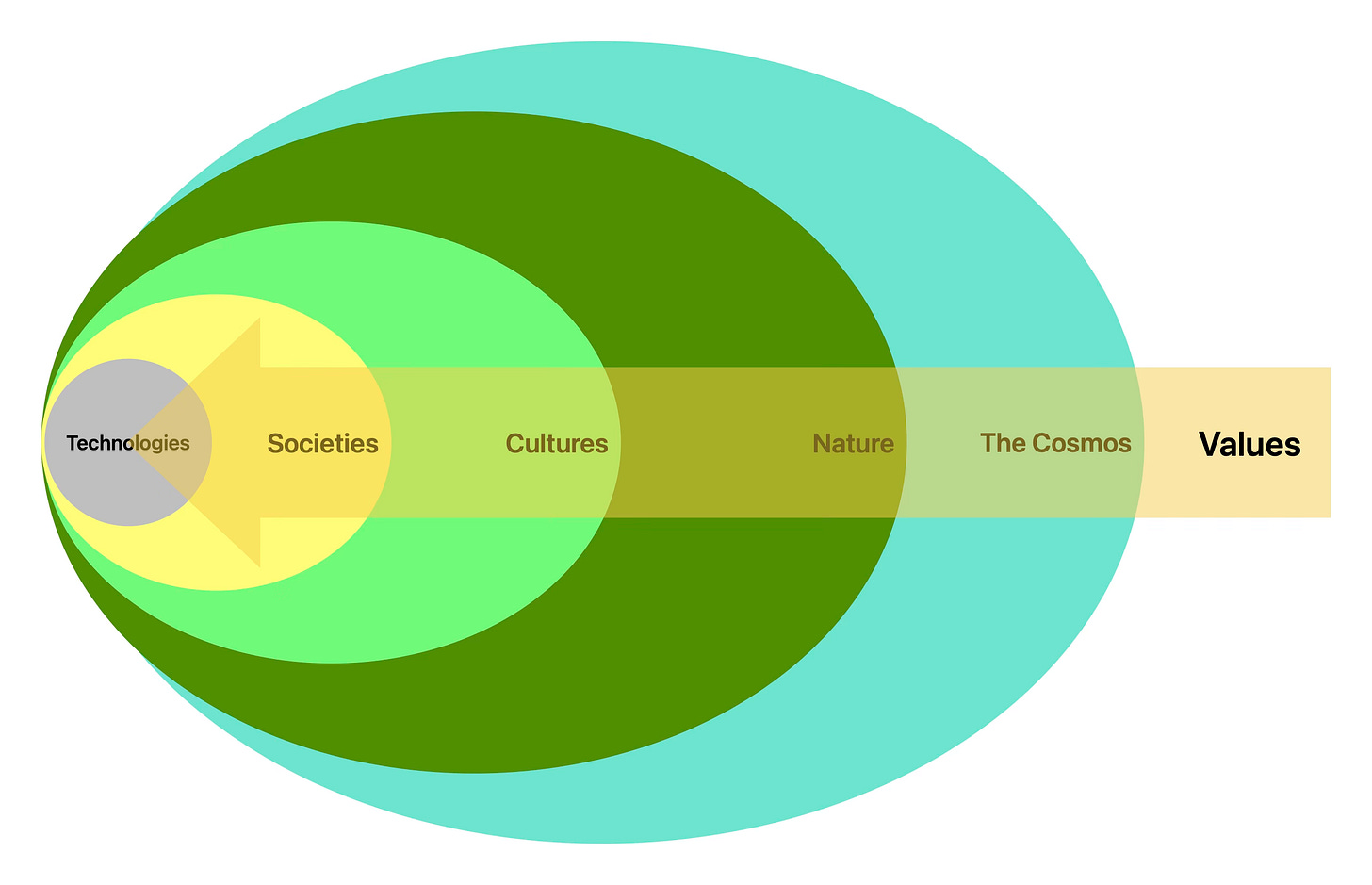

Once we get far enough in the complexities of technologies’ systemic impacts, we arrive at the peripheries of the system or ‘the superorganism’. There, we arrive at values, the values that ultimately drive the system. The illustration below is my crude attempt to capture this infinite process of movement.

Because technologies are human-made, unlike nature, we cling to them as testaments of our human exceptionality — an idea about exceptionality and separation from nature that is unfounded in many ways. Hence, any attempt at discerning a technological solution that is not good for ourselves and the planet, would need to be grounded in shared values that are not human-conceived either, but emanate from something bigger than us, namely nature — or, God, to those who are willing to equate the two, like I am.

The observation here is that values are discovered rather than invented, and life exists as a condition of value — Iain McGilchrist talks about value as intrinsic to the universe and how values come to play in everyday life through intuition; we intuitively perceive value when we see things in relations rather than as something separate. Therefore, machines cannot have values unless they have intuition, and they cannot have intuition as long as they do not have a past.

How might we deal with the loss?

The question of mourning began from one of Hine’s four questions, and I will close with returning to them. More precisely, to how they might need to be complemented and elaborated. Jay Cousins (

) has helpfully done some of this work already — in a discussion with Dougald, he articulated four additional questions:What should we put to use before we lose it?

What can we build/produce now, knowing that collapse is coming, that will help us better thrive in the ruins?

What can we evolve from the dying system?

What are the seeds of the things we mourn – and how do we harvest them?

Let’s address the last two in the context of mourning a technology. First, Cousins’ idea of the seeds and harvesting them: the seeds of a technology abandoned or lost might stem from loss of convenience and ‘fast’ culture, and harvesting them would mean privileging durability and local production that express care, connection, and community. Second, from the death of thoughtless convenience and disposability, what can be evolved? Perhaps a culture that acknowledges stillness, friction, and hardship as part of existence in nature. Ultimately, the combination of the two developments, harvesting and evolving, could lead to a more meaningful life.

I think the Amish might be on to something. Thank you for reading.

With love and kindness,

Aki

I love your work, and I always notice you have references to ideas/books I’ve not encountered before, which is unusual for me. Do you, by any chance, have a reading list for designers/technologists/etc, based on the works you’ve found most valuable?